|

Hi Thomas,

We'd be interested in seeing

older pictures in particular. Genealogy really is a massive project once

you get started. I'm pursuing a couple dozen lines at once. A web page

would be perfect -- and, if we're lucky, it would also attract other

Fe(c)skes that stumble upon it, maybe giving us both some clues. I found

a Hungarian Slovak genealogy online with an Anna Fecske from Bódvavendégi

(born 1878) that married into the family (almost surely your

great-grandfather's sister), and have written to the administrator about

that to see if I can get any more information on the family. Keep me

updated on that when it gets underway, OK?

I've also downloaded two reasonably detailed histories of the Fecskes'

ancestral village of Bódvavendégi/Host’ovce Slovakia

from the internet. One's in Hungarian and one's in Slovak. I intend to

translate (or at least summarize) both when I can find the time, which

is always the issue. My Slovak reading ability is OK, but the Hungarian

is more of a challenge. Anyhow, I'm forwarding both to you just in case

they're of any use to you in the meantime. They mostly say that lots of

Catholic Hungarians lived in the village and that many went to the U.S.

around 1900. :-)

I guess the secret is persistence. And experience; I know which

websites to hang out at, and just plug away with the searches until

something useful floats to the top.

Best wishes from Slovenia,

Don Reindl

|

History in Hungarian |

|

Source: Bodnár

Mónika 2002. Etnikai

és felekezeti viszonyok a Felső-Bódva völgyében a

20. században [Ethnic and Religious

Relations in

the Upper Bódva

Valley in the Twentieth

Century] (= Interethnica 1). Komárno: Fórum inštitút, pp. 101–105 (http://mek.niif.hu/01600/01604/01604.pdf)

Vendigi

Kisközség a történeti Torna vármegye felső

járásában, majd 1881 után Abaúj-Torna vármegye

tornai járásában. 1920–38 között, majd 1945 után

Csehszlovákiához csatolták. 1905-ben Bódvavendéginek

nevezték el, de a helyi szóhasználatban

napjainkig megmaradt a Vendégi vagy Vendigi. Szlovák

neve 1948-tól Host’ovce nad Bodvou. 1964-ben Nová

Bodva (Újbódva) néven összevonták a szomszédos

Horvátival és Újfaluval (Seresné 1983, 57; VSOS 2:

329). Napjainkban Szlovákiában a Kassa vidéki járásban

található. 1990 óta ismét önálló. Az 1773. évi

helységnévtár parókiával nem rendelkező magyar

faluként említi Vendigit (Lexicon Locorum 1920, 271),

bár egykori vendigi lelkészek feljegyzéseiből úgy

tudjuk, hogy templomuktól és iskolájuktól ...a

vendigii Reformatusok megfosztattak a régi időkben,

akkoron t. i. mikor ebben a nemes Torna megyében – a

mi Eklezsiaink nagy változást szennyvedtek –

Templomot elvétettek ... Tehát az ellenreformáció

korában Vendigi elveszítette anyaegyház mivoltát, s

a lenkei (Bódvalenke) anyaegyházhoz csatolták. Oda

tartozott egészen 1792-ig, amikor a Hernádbüdön

tartott papi konferencián a vendigi és ardai (Hidvégardó)

filiák a lenkei anyaegyháztól elváltak. Ekkor lett

Vendigi ismét anyaegyház, ...mivel ott már az

Oratorium és a Parokiális ház is készen volt. Ebből következik, hogy a reformáció

tanai itt is korán megjelentek és széles körben

elterjedtek, ám az ellenreformáció hatása is jelentősen

érvényesült. Egy 1806. évi egyházmegyei összeírásból

tudjuk, hogy a református lelkész helyben lakott, de a

reformátusok mellett római katolikusok és 12 görög

katolikus is élt a faluban. Ez utóbbiak prédikációs

nyelve a ruszin volt, s a horváti görög katolikus

anyaegyházhoz tartoztak (Udvari 1990, 87). Fényes Elek

a következőképpen írta le Vendigit: ...magyar

falu, a Bódva mellett, Tornához dél-nyugotra 1/2 órányira:

160 kath., 345 ref. lak. Ref. anyaszentegyház (Fényes

1851, IV: 290). Látjuk tehát, hogy a falu lakosságának

nagyobbik fele, több mint kétharmad része református

volt. A Borovszky-féle vármegye-monográfiában a

felekezeti megoszlás adatai nem szerepelnek, csak azt

tudhatjuk meg, hogy a századforduló előtti években

352 magyar lakosa volt (Borovszky–Sziklay 1896, 306).

A 20. század harmincas éveinek végén 419-en éltek a

faluban, akik 3 kivételével mind magyarok voltak. A

felekezeti megoszlást tekintve pedig 245 volt a

reformátusok,

164 a római katolikusok, 6 a görög katolikusok, 2 az

evangélikusok és 2 az izraeliták száma (Csíkvári

1939, 170). Az 1940. évi egyházlátogatási jegyzőkönyv

18. pontjának „megjegyzés“ rovatából tudjuk,

hogy az állami iskola tanítója volt evangélikus vallású.

Izraelitákra a 40-es években nem emlékeznek, valószínűleg

rövid ideig éltek csak Vendigiben. Azt viszont többen

is állítják, hogy a század elején éltek itt

zsidók,

temetőjük is volt a faluban, de ma már ez nincs meg.

Az amerikai kivándorlás nagyon elterjedt volt a

faluban. A Borovszky-féle vármegye- monográfia is

azon települések közé sorolta, ahol 1880–1890 között

szembeötlő mértékű volt a lakosság számának apadása

(Borovszky–Sziklay 1896, 368). A kivándorlási kedv a

későbbiekben sem hagyott alább, ennek fényes bizonyítékai

a presbitériumi jegyzőkönyvek, amelyek az 1889–1914

közötti években arról tanúskodnak, hogy az egyházközség

működése nehézkes volt, a presbiterek és egyházfiak

választása komoly problémát jelentett a gyakori kivándorlások

miatt.

Ám emellett azt is el kell mondani, hogy az amerikások

segítettek is egyházuknak, erről is tanúskodik az

egyházi irattár.

Kalydy Miklós feljegyzéseiből tudjuk, hogy a

vendigiek közül három család kivételével mindenki

járt Amerikában.

Voltak, akik végleg kinnmaradtak, de a legtöbben néhány

év után hazatértek. A férfiak zöme bányában

dolgozott, ám nemcsak férfiak, gyakran fiatal lányok

is szerencsét próbáltak. Volt aki háromszor is megjárta

Amerikát. Akik hazatértek, az összegyűjtött pénzből

általában földet vásároltak.

A második világháború utáni deportálások ezt a

falut elkerülték. Oroszországi kényszermunkára az

ittenieket nem vitték.

Ezt a helybéliek azzal magyarázzák, hogy a

faluban működő malomban szükség volt minden munkaerőre.

Csehországba sem deportáltak senkit, de a fiatalok közül

többen is elmentek munkát keresni. Néhányan ott is

maradtak. A magyarországi kitelepítés annyiban érintette

a falut, hogy több családot is szántak erre a sorsra,

akik kaptak úgynevezett fehér levelet, ám végül

mindnyájan maradhattak.

Lelkészüknek viszont menni kellett, ekkor telepítették

át Kalydy Miklós református lelkészt és családját.

Előbb csak a szomszéd faluba, Ardóba, ahol az iskolában

voltak elszállásolva. Kalydyékat teljesen váratlanul

érte a kitelepítés, éppen meszeltek, amikor megtudták,

hogy menniük kell, 50 kg-os csomagot vihettek magukkal.

Az ezt követő hetekben az egész falu, reformátusok,

katolikusok egyformán, folyamatosan csempészték át részükre

a szükséges holmikat, ágyat, ágyneműt stb. A

vendigiek napjainkban is tartják a kapcsolatot a családdal,

s ha valaki meglátogatja őket, mindenkiről, az egész

faluról érdeklődnek, nemcsak a reformátusokról. Ezt

annak bizonyságául mesélik, hogy itt nincsenek vallási

ellentétek. Az egyházi irattár tanúsága szerint

ugyan olykor kisebb összetűzésekre sor került a

katolikusok és reformátusok között, de mindig sikerült

megoldani a problémákat, azok soha nem fajultak el.

Napjainkra gyakoriakká váltak a vallási értelemben

vett vegyes házasságok, szinte már nincs is tiszta

református vagy tiszta katolikus család a faluban.

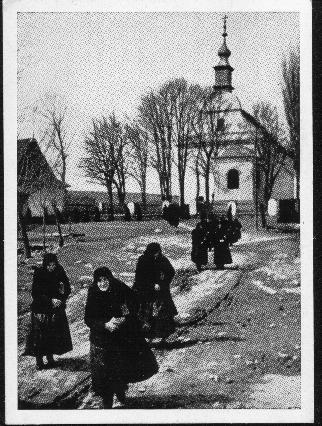

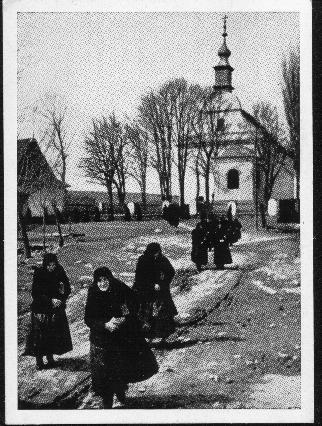

Vendigiben két templom van, a református II. József

Türelmi Rendelete után, 1787-ben épült a régi

harangláb helyén (Kováts 1942, II. 539). A katolikus

templom 1815-ben épült. A vendigi katolikus közösség

a második világháborút követő évekig az ardai

anyaegyház filiáját alkotta, de a határok meghúzása

végett kényszerűségből ezen változtatni kellett,

ma Újfaluhoz tartozik.

Az 1991. évi népszámlálás adatai szerint a

falu lakosságának vallási megoszlása a következőképpen

alakult: 124 volt a római katolikusok, 101 a reformátusok,

4 az evangélikusok száma, 1 görög katolikust írtak

össze, 5-en nem vallották magukat hívőnek, 6 esetben

pedig a vallási hovatartozás nem volt megállapítható.

Nemzetiségi összetételét tekintve az 1991. évi

adatok szerint a 241 lakosból 236 vallotta magát

magyarnak, 5 pedig szlováknak. Az 1993. évi adatok

szerint 226 magyart, 1 szlovákot, 1 sziléziait és 2

cigányt említenek. Ezek az adatok közel állnak a valósághoz,

ám mégsem fedik azt teljesen. A szlovákok számát

illetően nincs eltérés, egy-két szlovák menyecskét

tart számon a falu. Viszont a jelzettnél magasabb a

cigányok aránya, egyes becslések szerint 26 fő. Mind

rendesek, befogadta őket a falu. Vegyes házasságban

élnek a magyarokkal, akik általában környékbeliek.

Régen is éltek itt cigányok, a most itt élők

is az ő leszármazottaik. 1946-ban az egyik cigány

család félelmében elmenekült Magyarországra. A meglévő

cigányösszeírások is bizonyítják, hogy a megelőző

korokban is éltek Vendigiben cigányok. Az 1768. március

20-i összeírásban ugyan Vendigi nem szerepel, de egy

másik 1768-as összeírás szerint Gasparus Kuru nevű

mester élt a faluban. 1773-ban már két családot –

Gasparus Sándor és Gasparus Nanu – írtak öszsze,

mindketten mesterek voltak, de az utóbbi zenéléssel

is foglalkozott. Az 1854. évi összeírásban négy

családot említettek – Orgovány Zsiga (4 fő) éjjeli

őr, lúd pásztor; Orgovány József (1 fő) féllábú

katona; Orgovány Ferenc (2 fő) muzsikus; Samu Gábor

(3 fő) aprólékos munkás – útlevele egyiknek

sincs, és egyik sem kereskedik. A református egyház számtartókönyvében

is találunk rájuk utaló bejegyzéseket: 1818. október

14. Mikor a templom tetejét állítottuk, a klammerért

az ide való czigánynak fizettem ... –12; 1819. október

23. Sándor czigánynak 21 spernát szögért fizettem.

Vendigiben napjainkban a lakosok száma alig

haladja meg a kétszázat. Óvoda, iskola kb. húsz éve

nincs a faluban, amióta egyesítették a vendigi, horváti

és újfalusi intézményeket. Óvodába Újfaluba járnak,

autóbusz szállítja őket. Iskolába szintén Újfaluba

vagy Tornára utaznak. A mintegy húsz tanköteles

gyerek közül kb. öten járnak szlovák iskolába, a többi

magyarba. A faluban a magyar nyelvhasználat a jellemző

minden családban. Vendigi elöregedő falu, sokáig nem

volt lehetőség az építkezésre, ezért a fiatalok

legtöbbje elköltözött Szepsibe vagy Tornára.

Illés Dániel vendigi református prédikátor erre vonatkozó feljegyzései

1792-ből a vendigi református egyház irattárában

találhatók. A Sárospataki Egyháztörténeti Gyűjteményben

a vendigi református egyház történetére

vonatkozó adalékok Benkő Gáspár ev. ref. lelkésztől

1879. évből. Itt mondok köszönetet Pocsai

Eszternek, a gyűjtemény vezetőjének munkámhoz

nyújtott segítségéért.

Kifogásolandó az állami iskola evangélikus vallású tanítója és az

egyház közötti viszony. Megkeresendő a tanfelügyelőség,

hogy a ref. gyermekeknek az istentiszteletre való

felvezetése tétessék a tanító kötelességévé.

Kérelemmel kell fordulnia V. és K. Minisztériumhoz,

hogy az evangélikus férfi tanerő cseréltessék

ki reformátussal, ki a kántori teendőket is ellátná.

Egyházlátogatási jegyzőkönyv 1940. Vendigi

református egyházi irattár.

Zsidók a negyvenes években az én emlékezetem szerint nem éltek itt. De

korábban voltak. Édesapámék Siegel nevű családot

emlegettek. Volt itt zsidótemető is, de már nincs,

széthordták a márványt (Adatközlő: Balázs Irén,

sz. 1928).

Illusztrációként álljon itt néhány idézet:

1889. szeptember

25.: Nagy Sándor lelkész jelenti, hogy Zsóka

István gondnok minden szó nélkül itt hagyta az

egyházat s elköltözött Amerikába, felhívja a közgyűlést,

hogy miután gondnok választás válván szükségessé,

olyan gondnokot válasszanak, aki nem költözik ki

Amerikába, nehogy az egyház annak legyen kitéve,

hogy minden esztendőben új gondnokot válasszon.

1900. november

11.: Lelkész elnök felhívja a közgyűlést,

hogy ...Olasz Ferenc gondnok lemondása és Amerikába

távozása miatt ..., úgyszintén az Amerikába távozott

Balázs Ferenc lemondásával megüresedett másik

presbiteri állásra ...alkalmas egyéneket válasszon.

1903. január 2.:

Lelkész előadja, hogy a 15 éven felüli ifjak

a vasárnapi tanításért járó egy napszám munkát

vagy a lelkész fájának az udvaron való felvágását

az Amerikába való vándorlás miatt beállt munkáshiány

miatt nem teljesítik, s a lelkész drága pénzen kénytelen

a favágást eszközöltetni.

1904. március

5.: Ambrus János lelkész jelenti, hogy ifjú Cséplő

Ferenc az egyházfi szolgálatot ...útban lévén

Amerika felé nem fogadhatja el.

1912. július

21.: ...a presbitérium egy tagja Amerikába távozván,

helye betöltendő.

1914. június

14.: Lelkész előadja, hogy miután Mató István

egyházfi Amerikába távozott, új egyházfit kell

választani.

Presbitériumi jegyzőkönyvek I-II. Vendigi református egyházi irattár.

Az én tudomásom szerint a negyvenes években nem éltek itt zsidók. Zsidótemető

volt, nem nagy, vagy 12 sír volt benne (Adatközlő:

Szabóné Mázik Mária, sz. 1943 – tanítónő).

Az 1914. évi vagyonleltárban és az 1940. évi vagyontörzskönyvben

olvasható:

1 db úrasztali piros posztókendő (keresztelésre) - Amerikai Balázs István

emléke, 1902.

Presbitériumi jegyzőkönyv, 1903. november 29.: Lelkész jelenti, hogy

Szabó József Amerikából a lelkész által könyöradomány

gyűjtése céljából kiadott könyvre 461 korona

gyűjtött pénzt küldött.

1907. augusztus

4.: Olvastatik Bene István és Bene Ferenc

Amerikában tartózkodó híveinknek lelkésznek írott

szép levelük, melyben írják, miszerint

hallották,

hogy egyházunk orgonát építtetni szándékozik,

ők ugymond – e szándéknak a messzi távolban is

nagyon örülnek, s hogy örömüknek tettel is

kefejezést adjanak, gyűjtőkönyvet kérnek,

igérvén,

hogy tekintélyes összeget fognak e célra

gyűjteni.

A templomfelújításról szóló 1908.

november 29-i jegyzőkönyvből tudjuk, hogy az

orgona el is készült Ország Sándor rákospalotai

orgonaépítő által.

1923. november

24.: Lelkész előadja, hogy 2 évvel ezelőtt gyűjtőíveket

küldött Amerikába, amelynek eredménye a következő:

Balázs Gyula gyűjtött 1200 koronát, Zsóka

Ferenc 2000 koronát, Domonkos József 933 koronát

...

Bódvavendégiben 1941. július 27 – 1945. május 11-ig. Írta Kalydy

Miklós kiutasított lelkipásztor. Kézirat a Sárospataki

Kollégium Levéltárában. A kéziratot

kijegyzetelte 1978. szeptemberében Balázs Bálint,

akinek munkám során nyújtott segítségét ezúton

is köszönöm.

Adatközlők: Balázs Irén 1928., Szabóné Mázik Mária 1943., Balázs Bálint

1951. Balázs Bálint a szájhagyomány útján

megismert eseményeket novellisztikus formában

feldolgozta, megírta.

Mi is közéjük tartoztunk, de elszöktünk. Két napig tartott, közben

lefújták a kitelepítést. Vagy hat ilyen család

volt a faluban (Adatközlő: Szabóné Mázik Mária,

sz. 1943).

|

|

|

Additional

Fecske Information from Don Reindl

|

Grave

Search Results

9/5/2011

Search

for "Fecske" at Ancestry.com

http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gsr&GSfn=&GSmn=&GSln=Fecske&GSbyrel=all&GSby=&GSdyrel=all&GSdy=&GScntry=4&GSst=16&GScnty=705&GSgrid=&df=all&GSob=n

|

Fecske,

Anna Labuda  66979468

66979468

b. Dec. 8, 1879 d.

Mar. 10, 1953 |

Holy

Sepulchre Cemetery

Alsip

Cook County

Illinois, USA |

|

Fecske,

Barbara Kohl  66979146

66979146

b. Jul. 23, 1893 d.

Jan., 1978 |

Assumption

Catholic Cemet...

Glenwood

Cook County

Illinois, USA |

|

Fecske,

Ferencz  66979267

66979267

b. Dec. 29, 1890 d.

Jul., 1961 |

Assumption

Catholic Cemet...

Glenwood

Cook County

Illinois, USA |

|

Fecske,

Frank  66980158

66980158

b. unknown d. Nov.

9, 1913 |

Mount

Olivet Catholic Cem...

Chicago

Cook County

Illinois, USA |

|

Fecske,

Irene    66847371

66847371

b. Mar. 29, 1919 d.

Nov. 18, 1922 |

Mount

Olivet Catholic Cem...

Chicago

Cook County

Illinois, USA |

|

Fecske,

Joseph  66979520

66979520

b. Jan. 1, 1877 d.

Oct. 30, 1954 |

Holy

Sepulchre Cemetery

Alsip

Cook County

Illinois, USA |

|

Fecske,

Joseph C.  66979357

66979357

b. Mar. 29, 1907 d.

Feb., 1983 |

Assumption

Catholic Cemet...

Glenwood

Cook County

Illinois, USA |

|

Fecske,

Louis Edward  66978515

66978515

b. Dec. 6, 1930 d.

Dec. 9, 1930 |

Mount

Olivet Catholic Cem...

Chicago

Cook County

Illinois, USA |

|

Fecske,

Rose  67065985

67065985

b. Mar. 8, 1916 d.

Sep. 26, 1999 |

Saint

Mary Catholic Cemet...

Evergreen Park

Cook County

Illinois, USA |

|

Fecske,

William  67065941

67065941

b. Jul. 28, 1920 d.

Oct. 31, 1987 |

Saint

Mary Catholic Cemet...

Evergreen Park

Cook County

Illinois, USA |

|

| |

|

|

History in Slovak |

| KRÁTKA HISTÓRIA OBCE

Source: http://www.leader.rramoldava.sk/LEADER/HOSTOVCE/O3.htm

Územie

regiónu obývané od doby kamennej bolo križovatkou

obchodných ciest najmä z Dolnej zeme smerom na Spiš a

Poľsko. Od 13. storočia obec patrila do

Turnianskej stolice , neskôr župy až do roku 1848 keď

sa vytvorila

Abovsko-turnianska župa. Obec bola súčasťu

okresu Turňa Od roku 1923 patrila obec do dnes už

neexistujúceho okresu Moldava, ktorý bol v roku 1960

pričlenený k okresu Košice. Z okresu Košice sa v

roku 1968 vyčlenil okres Košice-vidiek , dnes

Košice-okolie.

V súčasnosti

obec patrí do okresu Košice-okolie, Košický samosprávyn

kraj. Je členom mikroregionálneho združenia obcí

- Združení Miest a obcí Údolia Bodvy s centrom v

Moldave nad Bodvou a Združenia miest a obcí Košice-okolie.

Prvá

písomna zmienka o obci je z roku 1263, keď je meno

obce zapísané ako villa Wendegy, vtedy ostihomský

arcibiskup prepustil desiatky z Torny a Vendégi, vtedy

tunajším farárom. Je teda zrejme, že obec bola už v

tom čase rozvinutou dedinou. Ale jej založenie je

staršie. Obec bola založená na území patriacom

Turnianskému hradu a v listine z 31.mája 1243 kráľ

Béla IV. oslobodil hosťov (vendég) bývajúcich v

Olassy de Tornava a udelil im privilégia. Smeli si

slobodne voliť richtára (villicus), ktorý mal súdiť

podľa zvyklosti hosťov. Dostali voľnú

ruku na udržovanie svojich zvyklostí a vymáhanie kráľovských

daní v takej výške, ako to bolo určené kráľom

Kalmánom určený, inak bratom Bélu IV. Táto

listina sa vzťahuje na dnešnú obec Hosťovce

a nie na Spišský Vlachov, ako sa donedávna domievalo.

Podľa legendy kráľ Béla IV. roku 1242 sa istý

čas zdržiaval v tomto kraji, býval v obciach

Gorgo (Hrhov) a Udvarnok (Dvorníky), včelárstvo

mal v Szádello (Zádiel) a Méhesz (Včeláre). V

našej obcivraj stála drevená krčma- hostinec, pre kráľa a jeho hostí,

kde ho tunajší obyvatelia vždy pohostili a kráľ

sem rád chodil. Odtiaľ meno obce. Inak po kráľovi

Bélovi IV. sa v okolí zachovalo množstvo legiend oa

pamätnných miest. Spočiatku boli dediny obce

zviazané s turianským domíniom a až po dostavbe

hradu Szádvár (v chotári obce Szogliget v Maďarsku)

sa stáva jeho majetkom. Hrad Szárvád bol postavený

po tatárskom vpáde (1241- 1242), ale prvýkrát je

doložený až v roku 1268 v listine podpísanej kráľom

Istvánom V. Podľa nej Tekusov súrodenec Bács

vydal hrad nepriateľom kráľa. Na konci 13

storočia hrad bol majetkom rodín Sziniovcov,

Szalonnaiovcova Jósvafoiovcov. Neskôr ho kráľ László

IV. či András III.vymenil za iné hrady. Kráľ

Károly Róbert hrad roku 1330 daroval svojím obľubencom,

jemu oddanej rodine Drugethovcov. Roku 1415 Szádvár

prešiel do rúk rodiny Bebekovcov (Pelsoczi) a tým aj

obec Bódvavendégi.

Okolo roku 1430 v obci žilo približne 480-500 obyvateľov(bolo

tu 30 port). V polovici 15 storočia hrad a panstvo

obsadili husiti, teda aj obyvatelia našej obce poznali

ukrutnosti tohto povstaleckého vojska. Ale roku 1454

ich vodca Péter Komorovsky ho vrátil Bebekovcom. Nakoľko

syn Imre Bebeka Pál zomrel bez potomka hradný majetok

Szádvár delila Obec od 13 storočia bola majetkom

mocného rodu Abovcov, ktorý v župe vlastnil rozsiahle

majetky. Neskôr bol tu zemepánom rod Bebekovcov. Vývoj

počtu obyvateľov roku 1939 -419 obyv. 1999-

208 obyvateľov, z ktorých je 97,51% maďarskej

národnosti. Žil a pracoval tu známy drevorezbár Ján

Béreš, vyrábal drobné malé náradie poľnohospodárske

potreby, mal aj výstavu. Dnes sú tieto výrobky vyložené

v Moldave nad Bodvou na mestkom úrade.Charakteristické

pre túto obec z minulosti je poľnohospodárstvo. K

dispozicí je kronika z roku 1947, mapy, staré

fotografie. Historické známe osobnosti pochádzajúce

z tejto obce: Fecske

Štefan profesor teológie, Ing. Vareš jozef profesor

strednej priemiselnej školy, Šolc Gejza mlynár, Béreš

Gábor farár. Nacházda sa tu reformovaný kostol z

roku 1787. V obci sa dodnes zachoval vodný mlyn, ktorý

slúžil obyvateľom celého údolia Bodvy.

|

|

|

|

New Information found by TCT October 3,

2011

trying to find

information on heritage Anna (Hoyer?)(Samko) Hegedus

Also, Labuda and

Fescke's came from this same area.

http://carpathiangerman.com/zipsancestry.htm

|

Carpathian

German Homepage

http://carpathiangerman.com/zipsancestry.htm |

MY ANCESTORS FROM THE ZIPS

A. WHERE IS ZIPS COUNTY

The ancestors of my mother's father came exclusively from

two small German towns in the Zips, Eisdorf and Zipser Bela.

This is a general introduction to the history and the customs of

the native Germans of the Zips. For the history of these two

towns, click:

Zips County (in Magyar Szepes Megye, slovakian S^pis), is in the

North-East of today's Slovak Republic. It is a high plateau

surrounded by Carpathians and the High Tatra, the Branisko chain

to the East and the Goellnitzer Erzgebirge to the South. The

main rivers are the Popper, Kundert (Hernad in Slovakian),

Goellnitz and Dunajetz. The village of Eisdorf in the Zips,

(Hungarian Iszakfalva or Zszakocz, Slovakian Zakovce in Spis),

all three meaning village of Isaac, probably the founder, but in

the 20th century often taken to mean "ice village," a

pun I often heard as a child from relatives who told me in the

village "nine months its winter there, the other three

months just cold") , is a small village about 8 km (or

5 miles) from the provincial center of Kaesmark (also spelled

Kesmark). The name of that city comes probably from old South

German Kes, meaning glacial, because set near mountains, and not

from cheese market (Kaese Markt). But one does not know for

certain and there are two interpretations. The Zips was

connected to the main agricultural area along the Gran through

the Kundert River. Eisdorf lies in a small wedge protected

(relatively speaking) against the icy winds from the Tatra

Mountains. It is one of the few Zips vilages without access to a

river, only a small brook crosses the village. Most of the

drinking water had to be taken from wells.

B. HISTORY OF ZIPS COUNTY

1. Prehistory to the Coming of Magyars and Slovaks:

The history of the Zips is hidden in the mist of time. There are

traces of people who lived there in the stone and the

bronze-ages. The first people of whom we know the names were the

Kotiner, who were Iberians. In the fifth century B.C. the Celts

conquered the area, and over time assimilated the conquered,

including the Kotiner. In the first century B.C. smaller German

tribes settled in the Zips, notably Sidonians, Naristians and

Buren. They had settlements on the sites of the future Kesmark

and Grossschlagendorf, notably. After the much larger German

tribes of the Quaden and Markomannen followed, the entire area

of today's Slovakia became Germanic. The Markomannen and Quaden

were often at war with the Roman Empire, and since Germans did

not yet use writing save for runes for short messages, all we

know about them was written by their Roman enemies. Rev. Rainer

Rudolf notes that surviving old charts from Neuendorf up to the

14th century name a small group of people living in an isolated

spot in the Goellnitz valley , the Chodener, who are

called neither Germans, Slavs nor Magyars. They probably were

the last remnants of the old Kotiner, who, though not using

their own Iberian language since over 1500 years, still were

dimly conscious of their tribal identity. Then they vanished,

assimilated by the surrounding peasantry. The Quaden were

virtually destroyed by the Romans in the late 4th century C.E.

Their remnants fled to the Zips fastness, and left with the

Langobarden, who were travelling through from the upper Vistula,

to conquer Northern Italy (Lombardy, the Land of the Langobards)

in 568 C.E. In 2005, the nearly intact grave of a germanic

chieftain from the early 5th century was found on the site of an

industrial park in Matzdorf, as reported by the Slovak

Spectator on November 6, 2006.

The situation after 568 C.E. is quite contentious among

modern historians. For some, the area was empty, a res

nullius, and hence its sole legitimate possessors are the

Slavic tribes that followed after the Germans left. But

archaeological finds--important for the centuries when few

written records were created, and even fewer survived--and the

transmission of Germanic place names, show that several thousand

Germans remained. But they were likely assimilated by the Slavs

over the next three centuries, when the area payed tribute to

the Turkic Avars. The Avars were beaten by the Frankish Empire

of Karl der Grosse (Charlemagne) in the Awar Wars from 791 and

803 C.E. As noted by Pater Rainer Rudolf in Zipser Land und

Leute, to secure the area, the Franks founded several

castles and villages in the Zips, notably on the site of

Arnoldsdorf (slv. Arnutovce) and Toppertz (from Theudeberts),

Mengsdorf and Lautschburg. From what is known from other Eastern

areas with Frankish border defense villages, these were

inhabited not only by German soldier-farmers, but by

Christianized Slavs as well. After the 9th century, very little

is known about the Zips for the next two centuries. Wild Magyar

horsemen tumbled down the Carpathian passes in the late 9th

century and conquered an area even larger than the Avar Empire:

The great Pannonian plain, and the mountains around it, from

Croatia in the South to Upper Hungary (future Slovakia) in the

North and Transylvania in the East.

In 907 the Magyars beat the German army decisively. In 991,

the Bavarian duke Heinrich der Zaenker (the quarrelsome)

destroyed the Magyar army. In between, the few German villages

left by the Carolingians in the 9th century may or may not have

perished. No document telling us survived. After the Magyars

became Christians, they wanted to develop their kingdom into a

modern state. But they were few in numbers. Their slavic

bondsmen were not numerous either after 4 centuries of constant

warfare. And neither group was accustomed to live in cities, nor

experienced in crafts and mining. The Magyars did not

effectively incorporate the Zips till the mid-11th century, when

they built their Gyepü (border stripes) settlements for border

soldiers (landzsasok) , and the North only in the late 12th. .

2. The First German Settlers: In old Hungary, save for

a small area of "clan land" taken by the seven Magyar

clans at the time of conquest, the king not just ruled, but

actually also owned the kingdom. Most of it was unsettled in the

early middle ages, (the entire population of the Hungarian

kingdom is estimated at 200,000 souls in the 10th century).

Subjects on that land, whether nobles or non-nobles, only

"owned" the hereditary right to use a certain

piece of land, subject to annual payments, or military service

in the case of tax-exempt nobles. The king could either remain

the direct lord of a settled area, which then was a "crown

land," and the peasants would pay to him the taxes owed to

him as king plus the rent owed to him as lord for the right to

till the land. Or he could assign his ownership rights rights to

a noble, to whom the peasants then owed the rent for the right

to till the soil. In exchange, the nobleman owed military

service and had to do all the administrative work for the king

for that area. In principle, he also owed the peasants, whether

serfs or free, maintenance in case of famine and protection from

outside enemies. To transform the forest into tax-producing

farms, the Hungarian kings distributed much land to nobles, who

then tried to get settlers. Some areas became royal cities (koenigliche

Freistaedte) that is received charters giving them autonomy and

putting them forever under direct royal rule. Most cities had

lesser rights--generally they were autonomous in their

administration, their burghers were not serfs, but often they

were subjected to the obligation to pay rent to nobles for the

land they used. There was no uniform code of laws then, and each

group of city-founders was able to negotiate more or less rights

for their city.

Well documented is the settlement of Germans in the Zips

County (Szepes Megye) during the reign of Geza II (r. 1142-1161)

and especially Andreas II (r. 1204-1235). In contrast to the

Germans of the Hauerland and Pressburg, whose dialect points to

bavarian-franconian origins, the Upper Zipser dialect points to

Northwest Germans (Lower Rhineland, Flanders) but who had

settled first in neighboring Silesia. In specific cases,

settlers came from other German areas as well, as in Eisdorf,

whose inhabitants were brought from the Eisacktal in South Tyrol

by their Lord, Bishop Ekbert of Andechs-Meran, who owned land in

South Tyrol and in the Zips. He also brought settlers from his

lands around Bamberg, whose bishop he was, such as to the lower

Zips, the Zipser Gruende, where the children of the Upper Zips

Germans intermingled with the Bavarian-Franconian miners. The

dialect of the Lower Zips is quite different from that of the

Upper Zips, while the area around Lublau, including Hopgarten,

spoke a Silesian German dialect. Their villages had been settled

by the Piasts from Krakau in Poland, until the border was set.

In the Zips, the first great landholder known to posterity

was the above-named Ekbert of Andechs-Meran. His sister Gertrud

was the wife of King Andreas II. Ekbert received from the king a

large chunk of the Zips around Gross-Lomnitz and Eisdorf. Ekbert

then granted the land to the Zipser abbot Adolf, whose sister

was married with the knight Rutker von Matrei, the ancestor of

the noble houses of Berzeviczy and Tharczay. The Berczeviczy

family received from the king further lands in the Zips and

founded the villages of Bierbrunn, Landeck, Altendorf,

Katzwinkel and many others. By 1241, about 4,000 people lived in

the Zips, mainly German settlers, plus about 1,000 Magyar border

guards and their Slovak bondsmen. The Mongol invasion of 1241 (Mongolensturm)

destroyed most of the settlements, German and Magyar, as well

archives. In the Zips, a century of work was destroyed, and

about half of the people killed by the Mongols. The others

survived a heroic siege on the Zufluchtsstein (Stone of Refuge,

Lapis Refugii), a fortified mountain plateau near Gross-Schlagendorf,

under their commander Jordan von Gargau, ancestor of the locally

important noble family of Görgey.

By now, the Kings of Hungary were more interested in making

this important border area well-populated. Slovak peasants were

settled from the neighboring Komitats. So were many new German

settlers, called by King Bela IV (r. 1235-1270). Together with

the survivors, they rebuilt the cities and villages. Having

performed heroically during the Mongol invasion, Jordan received

the old Carolingian village of Toppertz as seat, and went on to

found in the 13th century Malthern, Schoenwald, Kreig,

Scheuerberg, and Bauschendorf, as well as the mixed

Slavic-German village of Windschendorf (windisch=Slavic) .

Hungary was divided in counties, administered by a Gespann

and a county legislature made up of the local nobles. In 1271,

24 German cities of the Zips were consolidated into a German

autonomous area, the Zipser Staedtebund (city league) within the

Zips county, which remained autonomous till 1876 from the royal

county administration of Zips Megye, to which it continued to

belong otherwise. In that area of the Zips, the king remained

Lord, or had become Lord again in the troubled time after the

Mongol invasion. The Federation, for the annual payment of 300

Marks (one mark was about a half-pound) of pure silver and 50

soldiers, plus free food for the king and his court should they

visit, was freed from further financial obligations towards the

king--but not the nobles if their land was on land that was part

of a noble estate. The original 24 cities owed no rent to area

nobles. An important concession was that the governor of the

autonomous area, the Zipser Staedtebund, the count of the Zips,

(Zipser Graf), was not appointed by the king but elected for

life by an assembly of county notables, city mayors and priests.

The name remained though their number (including larger

villages) grew to 43 by 1312, some of which were on noble land.

Kesmark left the Bund in 1350, when it became a royal free city.

The rights of these cities were codified in the "Zipser

Willkür" in 1370 by king Ludwig I.

As a result, the county of the Zips, after its borders were

set in the 14th century having 3,605 km2 (1,442 sq. miles), was

split into several distinct administrative areas. These were the

self-governing Lanzentraeger villages, 10 of them (with 29

hamlets), with its Magyar nobles, the royal free cities of

Leutschau and Kesmark, and the the Saxon province with its 24

cities (of which 13 where mortgaged to Poland from 1412-1772).

The Lanzenträger lost their autonomie in 1804, the Zipser

cities in 1802, and the two royal free cities in 1876.

The original 24 cities of the Zipser Städtebund were Zipser

Bela, Leibitz, Menhard, Georgenberg, Deutschendorf, Michelsdorf,

Wallendorf, Zipser Neudorf, Rissdorf, Felka, Kirchdrauf,

Matzdorf, Durlsdorf (these 13 cities were mortgaged to Poland

from 1412-1772), Muehlenbach, Gross-Schlagendorf, Eisdorf,

Donnersmark, Schmoegen, Sperndorf, Kabsdorf, Kirn, Palmsdorf,

Eulenbach, and Dirn. In addition, there were five free royal

cities, Leutschau, Zeben, Bartfeld, Eperies, Kaschau, joined in

1350 by Kesmark. In the Southern Zips, seven German cities

formed the "Sieben Oberungarische Bergstädte" (Seven

Upper Hungarian Mining Towns' League), that is Zipser Neudorf,

(which also belonged to the 24-City League), Goellnitz,

Schmoellnitz, Rosenau, Jossau, Rudau and Telken.

Only about half of Zips county belonged to the Zipser Town

Federation. The other half, inhabited by Magyars, Germans and

Slovaks, on land either still owned directly by the king, or on

land granted to nobles or to cloisters (such as Schwenik),

remained under the standard county administration, paying taxes

to the king plus rent in cash and kind to the feudal lord who

had received manorial rights to an estate from the king. But in

1412, king Sigismund needed a large amount of cash quickly, and

borrowed it from the king of Poland. The loan was secured by

mortgaging the tax income of 13 of the 24 members of the Zipser

Städte Bund, including Zipser Bela, and the three cities

belonging to the royal estate of Alt-Lublau (Alt-Lublau, Pudlein

and Kniesen; these were old German cities but rather assimilated

by Slavs by the 15th century). The mortgaged cities legally

continued to belong to Hungary, but were administered by Polish

officials headquartered in the castle of Alt-Lublau. The Polish

administration lasted till 1772. The legal status of the cities

mortgaged to the Polish king remained "frozen" as it

was in 1412; they remained free from feudal dues to a lord. But

this mortgaging weakened the power of the 11 remaining Zipser

cities. In 1465, the king made the office of county head (Obergespann)

hereditary in certain families, in the Zips to the Zapolya,

followed by the Thurzo in 1536, and the Csaky in 1636. This did

not make the royal domains administered by that family their

property, unlike the holdings they had received as estate, but

in practice, the distinction between the two eroded. While at

first, taxes remained the same, they soon were hiked

arbitrarily. The 11 towns impovertished. When the 13 cities and

the 3 cities of the estate of Alt-Lublau were redeemed in 1772,

they could not be reunified anylonger with their 11 sister

cities because their legal and economic status was now so

different. Rather, the 16 mortgaged cities became a new Bund der

16 Zipser Städte, till its autonomy was abolished in 1876.

In 1526, the Hungarian army was destroyed at Mohacs, and its

king died on the battlefield, betrayed by the selfish nobles who

opposed his plans to streamline administration and curtail their

powers. The Hungarian capital was moved to Pressburg. The

hungarian nobles then elected the Habsburgs, who were dukes of

Austria and other territories, as well as elected Emperors of

Germany, also hereditary kings of Hungary.

3. Lost of Majority due to War and the Plague: The

German majority declined proportionally to Slavic inhabitants

beginning with the 15th century. There was the devastation left

by the Czech Hussites in the 15th century, the Turkish border

warfare in the 16th and 17th centuries, religious strife between

Protestants and the Catholic monarch (who were Emperors as

Emperors of Germany--there was no Emperor of Austria until

1803--and kings of Hungary), and the civil wars between pro- and

anti-Habsburg nobles. The latter had religious overtones as

well, since the anti-Habsburg forces were often Calvinists and

prepared to tolerate Lutherans (usually Carpathian Germans)

while the armies of the German--but more importantly, Catholic--

monarch, killed them as heretics. In 1606, the Emperor-King

allowed religious freedom to Protestants, but this promise was

not respected by his sharply Catholic successors. This, together

with other issues, led to uprisings led by mainly Calvinist

noblemen, with the support of the Lutheran German cities--with

the Turks always looming in the background. After an uprising by

Emmerich Thököly, Emperor Leopold I granted in 1681 at the

Landtag of Oedenburg a limited religious toleration. Protestants

as such were allowed to exist. But they were discriminated in

their right to hold public office, and could have only 2

churches per county (the so-called Articularkirchen, from

article 26 of the Treaty). These had to be entirely from wood

(even no nails allowed) and outside the city walls,

too--probably so that the Turks could burn them easily during

raids. There was a last, terrible convulsion in the area from

1683 to 1711. In 1683, the Turkish army laid siege to Vienna,

was beaten back with enormous loss of life, and by 1699 forced

out of most of Hungary. Upper Hungary was now free from the

threat of Turkish raids. Flush with victory, Leopold I rued his

1681 promise of religious toleration and began again to

persecute Protestants. The Protestant nobles revolted in 1703

until 1711, when in the peace of Szathmar the toleration of 1681

was confirmed. The Carpathian German cities were very hard hit

by these wars, and also by the plague, with that of 1710 killing

perhaps 7,000 Zipser, again more in the cities. Then, by the

17th century, most Catholic village priests (badly paid by the

state, and ill-educated) were Slovaks who promoted their

language among the villagers under their charge. The Tax Census

of 1720 showed, according to Joerg Hoensch, (2001) that Magyars

were still only 4% of the local population, but Germans now only

a small majority, and the rest Slovaks and Ruthenes. By 1790,

the Slavs had even become a slight majority. In 1781, Emperor

Joseph II in 1781 issued an edict of general religious tolerance

for all Lutherans in Hungary. He also encouraged some

immigration from the overpopulated Southwest of Germany to the

Dunajetz valley in the Northernmost Zips. But he also ordered in

1783 that all artisans, notwithstanding their religion or

ethnicity, should be made burghers, which threatened the

cultural cohesion of those cities that were still German and

restricted burghership to ethnic Germans, and Magyars and

Slovaks willing to intermarry and assimilate into the German

people.

For example, Karpfen, one of the oldest German cities

in the lower Zips, whose "Saxones de Corpona" (Saxons

from Karpfen) were noted in documents as early as 1135, was

destroyed by the Mongols, rebuilt, flourished, and then was

destroyed by the Hussites of Jan Jiskra in the late 15th

century. After the Hussites had been kicked out, to rebuild the

city, non-Germans were allowed to become burghers, too. The

first larger group of Slovaks moved into the city. Living in a

German environment, they were going to assimilate over the next

generations, but then came the Turkish wars that decimated the

local Germans. In 1566, Turkish raiders killed 2 burghers and

took 44 into slavery; in 1570, 20 burghers working their fields

were killed; another attack happened in 1578, and in 1582 over

200 Karpfen burghers were taken into slavery. For a small city,

these continuous losses were hard to make up. In 1611, Karpfen

elected a Magyar as mayor, the first non-German since the city's

foundation. In 1650, only 11 German children and 87 Slovak

children were born, noted from the language used at baptism. In

1673, the German Lutheran minister left the town, because the

flock had become too small to support him. By 1740, the great

Slovak historian Matthias Bel reported that only a few very old

people remembered that the city, now the Slovak city of Krupina,

once had German inhabitants.

Assimilation also happened in Menhard (Menhardsdorf), or

Vrbov in Slovak. Founded in the 13th century by German settlers

led by the Schultheiss (mayor) Meynhard (at the time, commoners

rarely had family names), it was a German village till the 19th

century despite being mortgaged to Poland from 1412 to 1778. In

1880, of 789 inhabitants, 736 were Germans, 35 Slovaks and 17

Jews (mainly German-speaking). But by 1940, of 870 inhabitants,

410 were Slovaks, 407 Germans, 7 Jews, and 52 others.

At the same time, the overpopulation of the farming areas led

many Zipser to emigrate already in the late 18th century to the Bukovina,

(Buchenland), notably the area of Zibau, where Zipser

German was spoken till World War II, to the area of today's

Karpato-Ukraine and of today's Maramures area in Romania,

(the Karpato-Ukraine includes part of the old Magyar county of

Marmaros, but also other counties such as Bereg), in the latter

notably the areas of Ober-Wischau and the nearby Wassertal

(Valea Vaser in Romanian). Zipser Saxons founded Oberwischau in

the 12th century as a mining settlement, but the original

population was assimilated over the centuries. The 18th century

migrants came mainly from the Oberzips, notably the area around

Kesmark and Leutschau, but also from Germany proper. Despite the

ethnic cleansing of the Germans of the East after World War II,

traces of Zipser famlies still survive in the Wassertal and

Oberwischau. This website here is in German, and has pictures

(2005) Oberwischau .

This emigration further reduced the number of Germans.

In 1847, the census counted 191,523 people in the Zips, of

which 63,833 were Germans, 2,043 Jews, 500 (!) Magyars, 98,951

Slovaks and 26,196 Ruthenians. The Germans, excluding Jews, were

now only 33% of the population. And after 1867, the urban

Germans increasingly became Magyars, owing to the pressure of

"magyarization" laws. In 1880, the census counted

172,881 people in the Zips. Of these 48,169 were German, 96,274

were Slovaks, 5,941 Jews, 16,158 were Ruthenians, and 3,526

Magyars. By 1910, the total number of inhabitants was 171,725

people, of which 38,434 were Germans, 7,475 Jews, 97,077

Slovaks, 12,327 Ruthenian, and 18,658 Magyar. Most of these

Magyars were former Germans. A good example of the ethnic change

was Zipser Bela, where, without any "ethnic

cleansing," from 1880 to 1890 the number of Germans fell by

19 percent, from 1890 to 1900 by another 8.3 percent, and from

1900 to 1910 by another 13.5 percent while the number of Magyars

exploded. (From Ladislaus Guszak, in Karpatenpost

February 1969, p. 4, based on census data in Dr. Erich Fausel, Das

Zipser Deutschtum, Jena, Germany, 1927, p. 111).

4. Burghers and Robots: Social Rank in the Zips: The

Zips had legally, till 1848, three classes of people. The nobles

owned the land and had a seat in the county legislature. They

were tax exempt. The local nobles tried from the 14th century

onwards to become feudal lords of the remaining royal areas.

They succeeded especially after 1526, when the new Habsburg

kings desperatly needed the support of the nobles against the

Turks. This included the remaining 11 cities of the Zipser

federation. While the people of these little cities kept their

local self-rule and were not made into serfs, (leibeigen) they

now had to pay the king's annual rent to a noble family. The

rent was raised substantially. The rent was due in cash and in

kind, and increasingly also unpaid labor, called the robot).

The Csaky remained hereditary Obergespann of the Zips till 1848,

and after that remained appointed county heads. Albin Csaky,

(1841-1912), who later served as minister of education in

Budapest, was Obergespann till 1880, the last of his family to

hold the office.

The Buerger, or burghers, of the remaining free royal cities

paid royal taxes collectively through these. Untertanen

(subjects) were the peasants and artisans of the villages and

small cities that had come under feudal rule. The most common

occupation, even in the towns, was that of peasant, called a

Untertan, Bauer, and in the 19th century a Landwirth, in latin

colonus. The Besiztlose, consisting of Hausleute, Kleinhaeusler,

Mietsleute etc were people without enough land to live from

farming. They eked out what their could from their garden plots

and worked as laborers or itinerant laborers or peddlers.

[To the top of the Webpage] 5. Torn

from the Fatherland: World War I and its aftermath: In

August 1914, World War I broke out. The Zips was administed in

1914 by Obergespann baron Arthur Wieland and Vizegespann Dr.

Ludwig Neogrady, in 1918 by Dr. Tibor von Mariassy. The Zips'

roughly 172,000 people, mainly small farmers, with some

industrial workers, could not expect to eke enough food from the

county's soil. The Russian offensive into Eastern Galicia in

Fall 1914 caused panic, with the front by September 26 at Tarnow

and Gorlice just East of Krakau--Tarnow was only about 160 km

(100 miles) from Kesmark--and also sent waves of refugees

crashing through the Popper River valley. But the German and

Austrian-Hungarian armies threw back the Russian army in

Mai-June 1915. After that, there was no direct military threat,

but the slow drain of young men and of food, the progressive

lack of which made death rates rise. Food production was

increasingly controlled by the Ministry for People's Nutrition (a.k.a

Food Ministry). It would be too much to detail the agony of the

Zips. I will focus on the last months of the war, based on the Karpathen-Post

and other sources.

By Summer 1918, the Zips was worn out. In late September, the

Food Ministry decreed that the Zips had to deliver at once 2,500

train wagons loads @5 tons of potatoes, or it be seized by

force. Also, a family could have only keep one pig per five

people to feed itself if they had a license. Sugar, one of the

few bountiful items, was raised from 2.14 K/kg to 2.92

wholesale, hence in stores from 2.40K to 3.30K. Even matches

were rationed. Local politics revolved nearly entirely in

lobbying for more food. Kesmark mayor Dr. Otto Wrchovszky

succeeded in getting the fat of 1,600 pigs to be rationed to the

nine Zipser cities with self-government. Also, after food

distribution broke down in November, and the Kesmark population

had nothing for December, he persuaded the local state

employees, who had received an annual allotment of flour and

other foodstuff, to share these, thus preventing mass starvation

(and probably the lynching of said employees by hungry mobs),

according to the Karpathen-Post of November 28.

Interestingly considering the times, in October-November, though

half of the mountain spas were closed, Tatraszeplak,

Ujtatrafured, and the sanatorium in Otatrafured, as well as some

hotels in Tatralomnitz,were still with guests from Budapest.

[This part is a work in progress]

6. The End after 800 Years: Slovakia became

independent in March 1939. In the great European civil war

between the two ideologies, its leaders allied themselves with

Hitler, who was not yet a mass-murderer in 1939, rather than

with Stalin, who had already murdered 15 to 20 million men,

women and children by that time. The Slovak Army participated in

the campaign against Poland and then against the Soviet Union.

Until 1943, when a German defeat appeared possible, few Slovaks

had complaints about that alliance, despite what their official

history claims today.

But as the tide of war turned, in Summer 1944, there was a

Communist-led partisan revolt in Central Slovakia. Over 3,000

ethnic Germans were massacred. The uprising failed. Yet, as the

Soviet Army rolled nearer, Carpathian German civilians were

evacuated to protect them from indiscriminate slaughter. The

children of Eisdorf were evacuated to Austria on September 21,

1944, led by their teachers, the boys to Glognitz and the

girls to Rabenstein. On January 10, most women and old

men, as other Germans from the Zips, were evacuated with the

last trains from the railroad station in Kaesmark. On January

23, the 85 men who had stayed packed their belongings on 55

carts, with 112 horses, and began a long trek through the

snow-covered and wolf- and partisan-infested countryside until

they reached Bischofsteinitz in the Sudetenland on February 25,

having trekked for 350 miles. Once the fighting was over, they

expected to be able to return to their little village. The trek

left in the nick of time. German and Hungarian troops (though

the Soviet imposed Hungarian puppet government, the so-called

"Debrecen government," had declared war on Germany on

December 21, 1944, most Hungarian troops fought with their

German friends and allies to the bitter end--such as in the epic

defense of Budapest till February 13, 1945)--evacuated the upper

Zips between January 22 to 26. Menhard was occupied by soldiers

from the Czechoslovak (Benes) army on January 27. So were the

other villages, by CSR and Soviet troops.

Not all Zipser left. Many simple souls, knowing they were

innocent, trusted the Allies (after all claiming to fight for

Freedom & Humanity), and stayed. Many were murdered by Czech

and Soviet troops. And when the war was over on May 8, 1945, the

great self-anointed humanitarians who claimed to fight a

"good war" allowed the Czech government to torture

some, kill others in slave labor camps, and ethnically cleanse

all of them from their homes of 800 years. Today, Eisdorf only

survives in the memories of families, such as mine, who live in

the Federal Republic of Germany, Austria, the United States and

Canada.

[To the top of the Webpage]

C. ZIPSER SPEECH

Carpathian Germans were divided by dialects that were not

mutually intelligible. Pressburger German was close to Viennese,

while Hauerlaender and Zipser were rather unique. In these two

regions, even people from other villages could have problems

communicating. In the Zips, the main difference was between the

dialect of the Oberzips, called Potoksch, and the dialect of the

Unterzips, called Mantakisch, while that of Kniesen and

Hopgarten in the uppermost NE of the Zips was closer to Lower

Silesian German. This example from the Oberzips is spelled

phonetically, using standard German phonemes.

A dancing song from the Zips

From Karpatenpost June 1968, p. j1.

Wu gejst hin, wu gejst hin, du schworzes Porailchen?

En die Mihl, en die Mihl, mein liebes Frailchen.

Wos sollst du en der Mihl, du schworzes Porailchen?

Mohln, mohln, mohln, mohln, mohln, mein liebes Frailchen.

Wos sollst med Mahl dank tun, du schworzes Porailchen?

Of mein Hochz, of mein Hochz, mein liebes Frailchen.

Wann wed dein schejn Hochz sein, du schworzes Porailchen?

Wanns Mihlchen pfeift, 's Korn a"uch reift, mein liebes

Frailchen.

[ To the top of the Webpage]

SOURCES ON THE ZIPS

Rudolf, Rainer, Pater, et alii, Zipser Land und Leute,

(Vienna, Austria: Karpatendeutsche Landsmannschaft 1982), esp.

45-60. Wanhoff, Adalbert. "Eisdorf, ein deutsches Dorf in

der Oberzips," Karpatenjahrbuch 1990, 77-88.

|

|

ZIPSER BELA HOMEPAGE

http://carpathiangerman.com/zipserbela.htm |

ZIPSER BELA HOMEPAGE

A. WHERE IS ZIPSER BELA?

Zipser Bela, in Magyar Szepesbela, in Slovak Spisska Bela,

often simply called “Bela,” or “die Bejl” in the German

dialect, is a town located about 7 Kilometers (4 American miles)

North of Kesmark, on the Western bank of the Popper/Poprad river

in the Oberzips, the Northern part of Zips county. The Zips was

part of Hungary till December 1918, then of Czechoslovakia, and

today of independent Slovakia. Many inhabitants were Germans

till 1945. In 2001, Zipser Bela had about 6,200 inhabitants, of

which 16 (0.26%) stated they were Germans in the last census.

There are probably another few who did not dare to admit their

ethnicity, after 50 years of oppression.

As most other towns of the Oberzips, Bela is on the high

plain between the towering Tatra mountains. Its median altitude

is 631 meters, about 2,000 feet. The town’s name derives from

the Bela creek, in Slavic meaning “white,” an appropriate

name for the gushing whitewater creek flowing through the town.

There were several such rivers in the old kingdom of Hungary,

and places named for them, hence informally "Zipser"

was added to Bela till it became official in the 20th century.

In the local German dialect, one did not say I go "nach

Bela" (to Zipser Bela) but "in die Bejl" (I go

into the Bela area).

B. BRIEF HISTORY OF ZIPSER BELA

A. From the Beginning till 1772

The first surviving charter naming the city dates from 1263,

when Bela IV, king of Hungary, awarded his faithful servant

Leonhard a piece of land bordering the German town of Bela. But

according to local historian Reverend Samuel Weber, a note

copied from an old mass book (provided it was not misread in the

Middle Ages) may indicate that Bela already had a chapel around

1072, while a 1416 court decision over a land dispute referred

to a decree from 1164 fixing the boundaries of the Slavic hamlet

of Bela and the German settlement of Valtendorf/ Waltendorf (for

Valentinsdorf), which later was lost. The latter’s village

church, St Valentin’s, was built in 1208. Eventually the

Slavic and the German settlements merged (as did nearby the

German Deutschendorf with the Slavic Poprad, for example). The

Mongol invasion of 1242-1243 destroyed all settlements,

including Bela, and virtually all documents. Few people and even

fewer documents survived. Therefore, very little is known about

the pre-Mongol era.

After the Mongols left, the Hungarian kings called new,

mainly German, settlers to the Zips. They mixed with the few

German and Slavic survivors and rebuilt towns and villages. Some

settlements were built on land the king had given to nobles.

Others, like Bela, were on land still owned directly by the

crown. Bela received city rights in 1271. Bela had an extensive

land area under its jurisdiction, for a small city, around 72

km2 (that is about. 28 square miles), including large forests

and pastures for cows and sheep in the mountains. Many burghers

were peasants, too, with fields outside the town. The mayor

(Richter) was elected directly by the burghers, as were the 6

Geschworenen (aldermen). As the city grew, a second church, St

Anthony’s, was added in 1264 to the rebuilt St Valentin’s.

Bela was a member of the league of 24 Zipser cities on crownland,

who paid an annual rent to the king for the land, and were

otherwise not subjected to the myriad of petty taxes and labor

dues burghers and peasant on noble lands owed their lord of the

manor. Bela’s Catholic priest was a member of the brotherhood

formed by the priests of these 24 cities. These were autonomous

from the Zipser provost (Probst). As in the rest of Christian

Europe, an important burden for subjects was the tithe. In

Hungary, all non-nobles had to pay the real tenth of their

annual income to the Catholic church, whose hierarchy also

determined its local beneficiary, the priest, without input from

believers, except when nobles had built and endowed the local

church, making then the church “patron” with the right of

veto over the bishop’s choice of a priest. But the burghers of

the Zipser cities were, which was rare in Europe, the patrons of

their own churches because they had built and endowed them with

land, whose income paid the priest. Hence the town owned the

tithe and the local parishioners elected their priest. As the

tithe was generous, the priest also had a powerful economic role

in the city.

In 1412, together with 12 other royal towns and the royal

domain of Lublau, Bela was mortgaged to the King of Poland. The

mortgage was supposed to last only for a few years, but ended

only in 1772. The King of Poland appointed a governor, the

Starost, to manage the income from his security deposit. He

lived in the castle in Lublau (for more details see the general

Zips History page). During the Polish era, Bela’s population

suffered like the rest of the Zips from epidemics and famines,

as well as fires. The city records noted 17 devastating fires

from the 16th to the 18th centuries, notably in 1518, 1521,

1551, 1553, 1607, 1667, and 1707. The plague struck hard in 1600

(700 dead), 1622 (175 dead), 1679 (418 dead), and especially

brutally in 1710. As a result, the town was smaller in the late

17th century than Eisdorf, for example, which most of the time

had been smaller. In 1674, the fee from Bela’s minister to the

Brotherhood was set at 3 Goldgulden, 66 Denare, while Eisdorf

paid 4 Goldgulden, 20 Denare, as did Zipser Neudorf and Menhard,

while Leibitz paid over 5 Goldgulden, and Leutschau 11.

The King of Poland gave the Starost a free hand as long as

the money flowed regularly. Initially, the king of Poland

changed Starosts at least once a generation, and kept them under

some control. But in 1596, needing the support of the powerful

Lubormirski family, he made them hereditary starosts of the

mortgaged cities, which they remained till 1745, when that

branch died out. The starostship then passed to a cadet branch

of the royal Poniatowski family and then to Count Brühl. The

Lubormirski owned of course much more land in the Kingdom of

Poland proper. Yet, because of its strategic location at the

Southern entrance to Poland, and the closeness of the Turkish

threat, since the border was near Kaschau till the reconquest of

Hungary in 1697, they paid close attention to the small

mortgaged Zips, through their castellan in Lublau.

At first little changed for the burghers of Bela, save the

address to send the royal taxes. But after a few decades, the

Starost began to interfere in local affairs. In 1460, the

Starost ordered that the mayors of all 13 cities be henceforth

not be elected by a general assembly of all burghers, but by

delegates elected by each ward, to limit the influence of poorer

craftsmen. But not all interferences were negative. Greatly

adding to Bela’s prosperity was the right to hold weekly local

markets every Sunday, awarded by the king of Poland in 1535, and

in 1607 the right to hold two annual regional fairs, on St

Anthony’s Day (January 7) and St. Matthias’ Day (September

21), increased to in 3 in 1667 and 5 in 1739. This benefited

Bela’s craftsmen. They formed numerous guilds since the middle

ages, notably butchers, shoemakers, dressmakers, furriers,

smiths and weavers. Flax was widely grown, and the linen made

from it sold throughout the Hungarian Kingdom. The town was

prosperous enough to build a new town hall in the 16th century.

However, the city had no regular town walls, never having

receiving royal permission for fortification, and for defense

relied on the adjoining stout backwalls of the burgher’s

barns, supplemented by wooden stockades. The town also had its

own militia, and those who could afford firearms trained since

1637 in the shooting society, the Schützenverein, which existed

till after World War I.

Concerning taxes, the Polish governor initially demanded only

what had been due to the King of Hungary, that is from the 13

cities their share of the Zipser city league tax, which in 1412

was for them 200 currency Mark in silver annually (at the time,

a good horse cost 4 Gulden, an ordinary house in Bela 12

Gulden), plus whatever was needed in case of war. This was

raised to 700 Gulden in 1674, which might reflect inflation and

currency changes. But the citizens were really hurt by a stream

of extraordinary levies, sometimes justified with the huge cost

of the Turkish wars, and sometimes simply by mailed fist. After

1541 another 300 Kuebel (one Kuebel was 125 liters, in US

measures 3.57 bushels @ 35 Liters) corn had to be paid jointly

by the 13 city parishes, after 1594 an additional 82 Florin in

cash, and then the corn tax was doubled to 600 Kuebel (or 2,143

bushels). In 1616 a new tax of 500 gold ducats, the Podor, was

imposed on the XIII cities, plus many smaller ad-hoc demands as

well. The worst period was under Theodor Constantin Lubomirski,

who ruled 1702-1745. He asked that the burghers start to pay

annually the Nona, the 9th of all goods, which was not only a

lot but also an insulting mark of servitude,. He then allowed

the cities to buy themselves free of this tax for 21,000 Gulden,

a very large sum, which they did. From 1714 to 1716 alone, about

181,000 Gulden were extorted from the 13 cities. The extortions

ceased after 1745.

The increasing oppression from the Starost also threatened

the religion of the inhabitants. The burghers of Zipser Bela

traditionally had the right to elect their own priest, who then

received a generous salary—but also had to pay the deacon and

the school teacher, and give a number of statutory gifts to the

Provost of the Zips, to the Hungarian count administering the

Zips, to the king of Hungary, and now to the Polish Starost as

well. The minister also had to help hosting distinguished guests

of the city in his stately parish house, and wine and dine them.

After the last Catholic priest of Bela Valentin Szontagh de

Bielitz died in 1545, the city elected a Lutheran priest as his

successor, Laurentius Quendel (called Serpilius), who was

actually a native of Bela. The whole city became Lutheran

without struggle. The reformation led to more public spending on

education. In the 16-17th centuries, the city school had three

teachers, the rector (usually with a degree from a German

university), an assistant teacher, and a cantor who taught

singing. The teachers were expected to participate in the city

festivities, write Latin speeches, etc., for free though the

cantor received additional fees for singing in church and at

funerals. In 1674, school taxes were thus: Each big house (there

were 173) paid 1 Kuebel grain, each small house (102) 0.5 Kuebel,

to the rector, a total of 224 Kuebel (800 US bushels), worth 220

Fl. There was no assistant teacher any more, but the rector had

to pay the cantor 12 Fl., and various other school employees 23

Florin, leaving 185 Florin for him. Collective worship was a

powerful expression of the town community. In 1565, the Starost

had promised to respect the free exercise of religion for

Lutherans in all XIII cities for an annual gift of 300 Kuebel

grain from the ministers, and 100 Dukaten from each newly

elected minister. The burghers of Bela worshipped fairly

unmolested after that, despite various anti-Lutheran policies

from the King of Hungary and the King of Poland, till the apex

of the counter-reformation in the late 17th century.

In June 1671, the King of Poland ordered the confiscation of

all Lutheran churches and schools, and the expulsion of all

Lutheran office holders from the XIII cities. But Starost

Hercalius Lubomirski did not implement the decree provided the

Lutheran cities now let Catholics worship freely, help them set

up churches and schools, and limit public office to Catholics.

However, under pressure from the Catholic clergy, in September

1672 he had to order the expulsion of Lutheran ministers who had

fled from other parts of the Zips. The pressure soon increased

dramatically, as the titular lord, the King of Hungary Leopold

II, now also demanded the suppression of Lutherans in the wake

of the Wesselenyi-conspiracy that rocked the Hungarian kingdom.

Leopold II ordered that all churches and schools, and the tithe,

be given to Catholics. In Bela, the church was handed over to

the Catholics and minister Johann Fontany expelled penniless

with his family. Ordinary local Lutherans were not expelled and

could still worship in their homes, though not without

molestation from various officials. Also, the Catholic priest

was now the sole public official recording births, deaths and

marriages, and received the fees for it. In 1700, the Starost

again allowed the cities to maintain Lutheran ministers, in

Zipser Bela it was Georg Roth, a native of Bela and son-in-law

of Fontany, but only for services in private homes. The Lutheran

ministers had to leave town right after services ended. This was

not enforced till Starost Theodor Lubormirski took power. On

August 10, 1703, in Kirchdrauf, the elderly minister Samuel

Platany was caught a few hours after services. The Starost had

him publicly whipped out of the city, and then banned all

private worship. But in 1707, for a considerable bribe, he

allowed a durable compromise. Private worship was allowed and

the minister could even live in the city. However, all Lutherans

services had to end at 8 AM, so that all Lutheran city officials

could attend Catholic services, which were mandatory for them.

The city school was seized in 1674, and Lutheran children had to

attend the now Catholic school. Home schooling was banned, as

was sending children outside the 13 cities area for education.

In 1758 Starost count Theodor Brühl allowed some Lutheran home

schooling but in 1771 Starost Poniatowski banned it again.

Overall, though Poland and Hungary pursued sharp re-catholization

policies, it was in the Starosts’ material interest not to

harm the economic viability of the XIII cities, and to attract

loyalty by being a tad more liberal than the ultra-Catholic

Csaky who ruled the part of the Zips that remained under direct

Hungarian rule. Incidentally, these oppressive policies did not

lead many people to switch their faith, noted Reverend Samuel

Weber, who from his parish registers counted about 30 adults who

became Catholics from 1674 to 1781, mostly to marry, as

Catholics who converted risked the death penalty.

B. From 1772 to World War I:

In 1772, the Polish administration ended. As the old medieval

league of XXIV cities could not be recreated, the XIII redeemed

royal cities, plus the three towns in the royal domain of Lublau,

were merged as the XVI Zipser City League. Save for 1785-1790,

when the district was abolished, the league retained its

autonomous administration till 1876. However, they had to give

up their Saxon inheritance law (which preserved property in the

hands of one heir) for Hungarian law, were everything was

divided among all. Initially, Maria Theresia’s rule brought

more restrictions to local Lutherans. But after Joseph II issued

in 1781 his patent tolerating the Lutheran (and other)

religions, allowing them to keep their own parish records, the

Lutheran parish of Zipser Bela was organized in 1782. The parish

was joined by the peasants of the nearby villages of Kreutz (Keresztfalu

in Magyar, Krizova Ves in Slovak) and Nehre (in Magyar Nagyor,

in Slovak Strazky), whose noble landowners, the Lutheran family

Horvath Stansith de Gradecz, preferred to affiliate their

Lutheran peasants with Bela rather than have to create and endow

separate parishes. Kreutz had been a German village till the

late 17th century, but was now Slovak, while Nehre was still

German, and as late as 1930 to 65%. The Bela Lutheran parish

registers begin with 1783. The Bela Lutherans now collected

3,000 Gulden to build a church, and also did much of the labor

themselves. Begun in 1784 on three plots donated by the Schmeiss,

Gulden and Kaltstein families, the Lutheran church was

inaugurated 1786. Yet the Catholic county officials hindered

them often. In 1818 the parish built a Totenhaus in its corner

of the cemetery. The county authorities had it torn down, and

also forbade the creation of a Lutheran poor house in 1832.

Also, St Anthony’s still held the right to tithe all burghers,

no matter their confession, till the right was redeemed in 1848

for 1,800 Gulden.

The attitude of the Catholic county administration also

affected the school after 1772. First the Hungarian officials

simply forbade Lutheran schools, claiming they were bound to

honor Poniatowski’s edict. Then, in 1780, “national

schools” (public grade schools with a national curriculum)

were created, in theory non-denominational except for religion

and singing provided by the respective Catholic and Lutheran

parishes. But in practice only Catholic teachers were hired. In

1785, Josef II allowed Lutheran schools, and the local Lutherans

opened their own grade school. In 1802, teacher Martin Lang

received a free apartment in the school house and use of a

vegetable patch, 150 Gulden (Florin, Fl.) in cash and 6 Metzen

corn, mainly rye, (10.71 bushel), 8 Klafter firewood (a Klafter

had 3 cubic meters, or 83% of a US cord, it was 6 2/3rd cords

total), but he had to cut and cart the logs himself. He also

received sundry fees from each child, such as a 10 Kreuzer

registration fee and a 6 Kreuzer on his name day and certain

holidays, altogether estimated by Samuel Weber at 50 Fl. over

the year. The teacher had to substitute for the minister if the

latter was sick for free, but earned additional money by doing

the organizational work at funerals, incl. writing the funeral

oration. If he had the training (and strength) to also work as

the parish cantor, he could earn another 80 Fl. salary, plus

fees for organizing the singing at marriages and funerals. In

1842 mandatory Latin was dropped from the grade school

curriculum, but drawing, geometry, mapmaking, gymnastics, and

Hungarian, added to it and the teaching method changed from rote

learning to more active student learning.

The aftermath of the revolution of 1848/49 brought full legal

equality, and also led to a change of attitude among the local

Catholic Magyar nobles who enforced that law. Local Germans, in

Zipser Bela and elsewhere, had supported the Magyar

revolutionaries against the Hapsburgs. After the revolution was

over, Bela Lutheran minister Karl Maday was even briefly jailed

(He later became bishop). The Catholic Hungarian nobles took

note. And so religious strife lessened over time and in 1870 the

Bela Lutherans gave up their parish school to join the reformed

public school, which also hired the four Lutheran teachers.

After 1870 grade school teachers were lavishly paid, receiving

still free lodging with a large garden, but now 400 Gulden in

cash (US-$ 160 then), 12 Klafter firewood (about 10 US cords),

with free cutting and carting now, and still a small cash gift

from each child on name day. They were morally expected to be

active in their parish, but not forced anylonger to act as

clerical help to the minister. However, they now were expected

to be agents of Magyarization. Two important persons in Bela

during that era were Rev. Samuel Weber (1835 Poprad-1908 Bela),

Lutheran minister in Bela from 1861 to 1908, and his successor

Franz Ratzenberger (1863 Schwedler-1930). Both were literary

active and wrote on local history as well. Weber was honored by

the city in 2008. Unfortunately in the exhibit the names of his

family were “Slovakized” though his ancestors were all

Zipser Saxons, giving a misleading impression of how he saw

himself.

The economic situation of Bela remained good throughout the