|

Hungarian People

| Hungarian People

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magyars |

Hungarians, also known as MagyarsHungarian:

magyar (singular);

magyarok (plural)are a nation

and ethnic

group who speak Hungarian

and are primarily associated with Hungary.

There are around 14-15 million Hungarians, of whom 10 million

live in today's Hungary (as of 2011).[19]

About 2.2 million Hungarians live in areas that were part of the

Kingdom

of Hungary before the 1918-1920 dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian

Monarchy and the Treaty

of Trianon, and are now parts of Hungary's seven

neighbouring countries, especially Romania,

Slovakia,

Serbia

and Ukraine.

Significant

groups of people with Hungarian ancestry live in various

other parts of the world, most of them in the United

States, Germany,

the United

Kingdom, Brazil,

Argentina,

Chile,

Canada

and Australia.

The Hungarians can be classified into several subgroups

according to local linguistic and cultural characteristics;

subgroups with distinct identities include the Székely,

the Csángó,

the Palóc,

and the Jassic

people.

Name

The exonym

"Hungarian" is thought to be derived from the Bulgar-Turkic

On-Ogur

(meaning "ten" Ogurs),[20]

which was the name of the Utigur

Bulgar

tribal confederacy that ruled the eastern parts of Hungary after

the Avars,

and prior to the arrival of Magyars. The Hungarians must have

belonged to the Onogur tribal alliance and it is quite possible

they became its ethnic majority.[20]

In the Early

Middle Ages the Hungarians had many different names, such as

"Ungar" or "Hungarus".[21]

The Hungarian people refer to themselves by the denomination

"Magyar", and not the term "Hungarian",

which is only used by non-Hungarians.[20]

The "H-" prefix is an addition in Medieval

Latin. The medieval

Kingdom of Hungary was known in Latin as either Regnum

Hungariae or as Regnum Ungariae.

The Hungarian endonym

is Magyar. There are several theories about the origin

and meaning of the word "Magyar".[

Ethnic

affiliations and genetic origins

The linguistic heritage of the Hungarians comes from Finno-Ugric

peoples. A branch of Uralic speakers migrated from their

original homeland near the Ural mountains and settled in

various places in eastern Europe, until they conquered the

present-day area of Hungary between the 9th and 10th centuries.

Genetically, the present-day Hungarian population preserves much

of an older European genetic makeup.[22][23]

In the Middle

Ages, according to genetic and palaeoanthropological

studies, the majority of Hungarians showed features of European

biological descent.[24][

Pre-fourth

century AD

During the fourth millennium BC, the Uralic-speaking

peoples who were living in the central and southern regions of

the Urals

split up. Some dispersed towards the west and northwest and came

into contact with Iranian speakers who were spreading

northwards.[26]

From at least 2000 BC onwards, the Ugrian speakers became

distinguished from the rest of the Uralic community. Judging by

evidence from burial mounds and settlement sites, they

interacted with the Andronovo

Culture,[27]

furthermore, the type of Hungarians of the Conquest period shows

related features to that of the Andronovo people.[28]

Fourth

century to c.830 AD

In the fourth and 5th centuries AD, the Magyars moved to the

west of the Ural Mountains to the area between the southern Ural

Mountains and the Volga

River known as Bashkiria (Bashkortostan)

and Perm

Krai.

In the early 8th century, some of the Magyars moved to the Don

River to an area between the Volga, Don and the Seversky

Donets rivers.[29]

Meanwhile, the descendants of those Magyars who stayed in Bashkiria

remained there as late as 1241.

The Magyars around the Don River were subordinates of the Khazar

khaganate.

Their neighbours were the archaeological Saltov

Culture, i.e. Bulgars

(Proto-Bulgarians, Onogurs)

and the Alans,

from whom they learned gardening, elements of cattle breeding

and of agriculture. Tradition holds that the Magyars were

organized in a confederacy of tribes called hétmagyar

(lit. seven Hungarians). The tribes of the hétmagyar

were: Jenő, Kér, Keszi, Kürt-Gyarmat,

Megyer, Nyék, and Tarján.

c.830

to c.895

Around 830, a civil war broke out in the Khazar

khaganate. As a result, three Kabar

tribes[30]

of the Khazars joined the Magyars and they moved to what the

Magyars call the Etelköz,

i.e. the territory between the Carpathians

and the Dnieper

River (today's Ukraine)[citation

needed]. Around 854, the Magyars faced a

first attack by the Pechenegs.[29]

(According to other sources, the reason for the departure of the

Magyars to Etelköz was the attack of the Pechenegs.) Both the

Kabars and earlier the Bulgars

may have taught the Magyars their Turkic

languages. The new neighbours of the Magyars were the Varangians

and the eastern Slavs.

From 862 onwards, the Magyars (already referred to as the Ungri)

along with their allies, the Kabars, started a series of looting

raids from the Etelköz

to the Carpathian Basinmostly against the Eastern

Frankish Empire (Germany) and Great

Moravia, but also against the Balaton

principality and Bulgaria.[31]

Entering

the Carpathian Basin (c.895)

In 895/896, under the leadership of Árpád,

some Hungarians crossed the Carpathians

and entered the Carpathian

Basin. The tribe called Megyer was the leading tribe of the

Hungarian alliance that conquered the centre of the basin. At the

same time (c.895), due to their involvement in the 894896

Bulgaro-Byzantine

war, Magyars in Etelköz were attacked by Bulgaria

and then by their old enemies the Pechenegs. The Bulgarians

won the decisive battle

of Southern Buh. It is uncertain whether or not those

conflicts were the cause of the Hungarian departure from Etelköz.

From the upper Tisza

region of the Carpathian Basin, the Hungarians intensified their

looting raids across continental Europe. In 900, they moved from

the upper Tisza river to Transdanubia (Pannonia)[citation

needed], which later became the core of the

arising Hungarian state. At the time of the Hungarian migration,

the land was inhabited only by a sparse population of Slavs,

numbering about 200,000,[29]

who were either assimilated or enslaved by the Hungarians.[29]

After the battle of Augsburg (955), the Hungarians stopped

their raids against Western Europe.

Many of the Hungarians, however, remained to the north of the

Carpathians after 895/896, as archaeological findings suggest

(e.g. Polish

Przemyśl).

They seem to have joined the other Hungarians in 900. There is

also a consistent Hungarian population in Transylvania,

the Székelys,

comprise 40% of the Hungarians

in Romania.[32][33]

The Székely people's origin, and in particular the time of their

settlement in Transylvania, is a matter of historical controversy.

History

after 900

Medieval Hungary controlled more territory than medieval

France, and the population of medieval Hungary was the third

largest of any country in Europe.

The Hungarian leader Árpád

is believed to have led the Hungarians into the Carpathian

Basin in 896. In 907, the Hungarians destroyed a Bavarian

army in the Battle

of Pressburg and laid the territories of present-day Germany,

France and Italy open to Hungarian raids. These raids were fast

and devastating. The Hungarians defeated Louis

the Child's Imperial Army near Augsburg

in 910. From 917 to 925, Hungarians raided through Basle,

Alsace,

Burgundy,

Saxony,

and Provence.[34]

Magyar expansion was checked at the Battle

of Lechfeld in 955. Although the battle at Lechfeld stopped

the Hungarian raids against Western

Europe, the raids on the Balkan

Peninsula continued until 970.[35]

Hungarian settlement in the area was approved by the Pope

when their leaders accepted Christianity,

and Stephen

I the Saint (Szent István) was crowned King of Hungary

in 1001. The century between the Magyars' arrival from the eastern

European plains and the consolidation of the Kingdom

of Hungary in 1001 was dominated by pillaging campaigns across

Europe, from Dania (Denmark)

to the Iberian

Peninsula (modern Spain and Portugal).[36]

After the country's acceptance into Christian Europe under Stephen

I, Hungary served as a bulwark against further invasions from the

east and south, especially against the Turks.

At this time, the Hungarian nation numbered between 25,000[37]

and 1,000,000 people.[29][38]

The name "Hungarian" has also a wider meaning, as it

once referred to all inhabitants of the Kingdom

of Hungary irrespective of their ethnicity.[39]

The first accurate measurements of the population of the

Kingdom of Hungary including ethnic composition were carried out

in 185051. There is a debate among Hungarian and non-Hungarian

(especially Slovak and Romanian)

historians about the possible changes in the ethnic structure

throughout history.

Some historians support the theory that the Magyars' proportion

in the Carpathian Basin was at an almost constant 80% during the Middle

Ages[40][41][42][43][44]

non Magyars numbered hardly more than 20% to 25% of the total

population[40]

and began to decrease only at the time of the Ottoman

conquest,[40][41][44]

reaching as low as around 39% in the end of the 18th century.

The decline of the Magyars was due to the constant wars, Ottoman

raids, famines and plagues during the 150 years of Ottoman rule.[40][41][44]

The main zones of war were the territories inhabited by the

Magyars, so the death toll attrited them at a much higher rate

than among other nationalities.[40][44]

In the 18th century their proportion declined further because of

the influx of new settlers from Europe, especially Slovaks,

Serbs,

Croats[citation

needed], and Germans.[40][41][44][45]

Droves of Romanians entered Transylvania during the same period.[41][45][46]

As a consequence of the Turkish occupation and the Habsburg

colonization policies, the country underwent a great change[citation

needed] in ethnic composition.[44]

Hungary's population more than tripled to 8 million between 1720

and 1787, however, only 39% of its people were Magyars, who lived

primarily in the centre of the country.[40][41][42]

Other historians, particularly Slovak and Romanian ones, tend

to argue that the drastic change in the ethnic structure

hypothesized by Hungarian historians in fact did not occur.

Therefore, the Magyars are supposed to have accounted only for

about 3040%[citation

needed] of the Kingdom's population since its

establishment. In particular, there is a fierce debate among

Magyar and Romanian historians about the ethnic composition of Transylvania

through the times; see Origin

of the Romanians.

In the 19th century, the proportion of Magyars in the Kingdom

of Hungary rose gradually, reaching over 50% by 1900 due to higher

natural growth and magyarization.

Between 1787 and 1910 number of ethnic Hungarians rose from 2.3

million to 10.2 million due to population

explosion, generated by the resettlement of the Great

Hungarian Plain and Voivodina

by mainly Roman

Catholic Hungarian settlers from the northern and western

counties of the Kingdom of Hungary. In 1715 (after the Ottoman

occupation) the Southern

Great Plain was near uninhabited, now has 1.3 million

inhabitants, and it's homogeneous with ethnic Hungarians.

Spontaneous assimilation was an important factor, especially

among the German and Jewish minorities and the citizens of the

bigger towns. On the other hand, about 1.5 million people (of whom

about two-thirds were non-Hungarian) left the Kingdom

of Hungary between 18901910 to escape from poverty.[47]

The years 1918 to 1920 were a turning point in the Magyars'

history. By the Treaty

of Trianon, the Kingdom had been cut into several parts,

leaving only a quarter of its original size. One third of the

Magyars became minorities in the neighbouring countries.[48]

During the remainder of the 20th century, the Magyar population of

Hungary grew from 7.1 million (1920) to around 10.4 million

(1980), despite losses during the Second

World War and the wave of emigration after the attempted revolution

in 1956. The number of Hungarians in the neighbouring

countries tended to remain the same or slightly decreased, mostly

due to assimilation (sometimes forced; see Slovakization

and Romanianization)[49][50][51]

and emigration to Hungary (in the 1990s, especially from Transylvania

and Vojvodina).

After the "baby

boom" of the 1950s (Ratkó era), a serious

demographic crisis began to develop in Hungary and its neighbours.[52]

The Magyar population reached its maximum in 1980, after which it

began to decline. This decline is expected to continue at least

until 2050, at which time the population will probably be between

8 and 9 million.[52]

Today, the Magyars represent around 35% of the population of

the Carpathian Basin, their number is around 1213 million. For

historical reasons (see Treaty

of Trianon), significant Hungarian

minority populations can be found in the surrounding countries,

most of them in Romania

(in Transylvania),

Slovakia,

Serbia

(in Vojvodina).

Sizable minorities live also in Ukraine

(in Transcarpathia),

Croatia

(primarily Slavonia)

and Austria

(in Burgenland).

Slovenia

is also host to a number of ethnic Hungarians, and Hungarian

language has an official status in parts of the Prekmurje

region. Today, more than two million ethnic Hungarians live in

nearby countries.[53]

There was a referendum

in Hungary in December 2004 on whether to grant Hungarian citizenship

to Magyars living outside Hungary's borders (i.e. without

requiring a permanent residence in Hungary). The referendum failed

due to insufficient voter

turnout. On May 26, 2010, Hungary's Parliament passed a bill

granting dual citizenship to ethnic Hungarians living outside of

Hungary. The neighboring countries with sizable Hungarian minority

expressed concerns over the legislation[54].

Later

influences

Besides the various peoples mentioned above, the

Magyars assimilated or were influenced by subsequent peoples

arriving in the Carpathian Basin. Among these are the Cumans,

Pechenegs,

Jazones,

Germans

and other Western European settlers in the Middle

Ages. Vlachs

(Romanians)

and Slavs

have lived together and blended with Magyars since early medieval

times. Ottomans,

who occupied the central part of Hungary from c.1526 until c.1699,

inevitably exerted an influence, as did the various nations (Germans,

Slovaks,

Serbs,

Croats

and others) that resettled depopulated territories after their

departure. Similar to other European countries, Jewish,

Armenians,

and Roma

(Gypsy) minorities have been living in Hungary since the Middle

Ages.

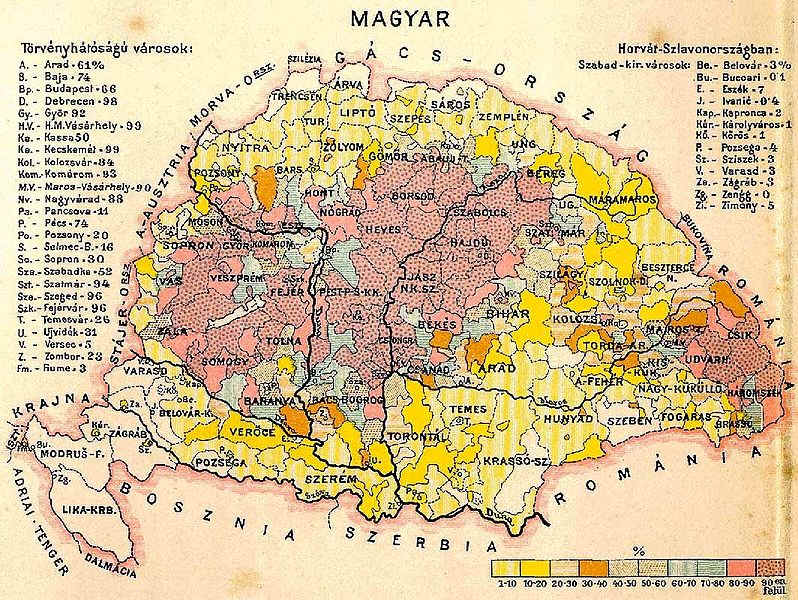

Hungarians in Greater

Hungary

(census 1890) |

|

|

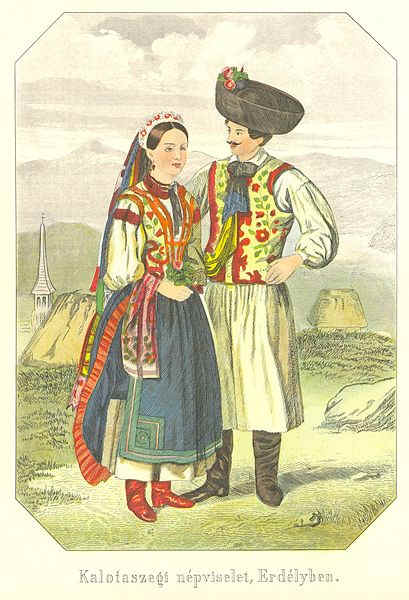

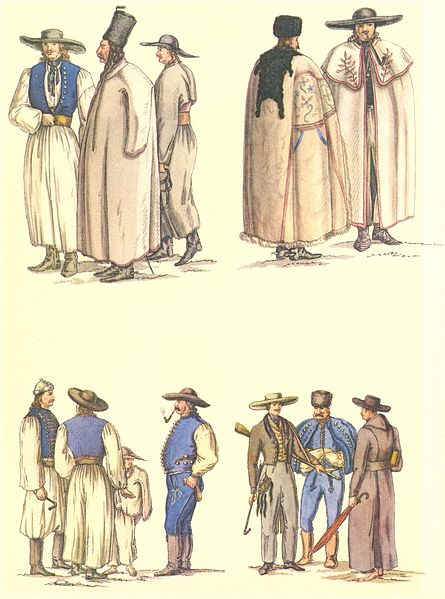

Traditional

costumes (17th and 18th century) |

|

|

Traditional

costumes (17th and 18th century) |

|

|

Traditional

costumes (17th and 18th century) |

|

|

| Kingdom of

Hungary

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Hungary |

The Kingdom of Hungary was a multilingual,

multiethnic

and (as the meaning from the 19th century) multinational[4]

country in Central

Europe covering what is today Hungary,

Slovakia,

Transylvania

(now part of Romania),

Carpathian

Ruthenia (now part of Ukraine),

Vojvodina

(now part of Serbia),

Burgenland

(now part of Austria),

and other smaller territories surrounding present-day Hungary's

borders. From 1102 it also included Croatia

(except Istria),

being in personal

union with it, united under the Hungarian king. The kingdom

existed for almost one thousand years (10001918 and

19201946) and at various points was regarded as one of the cultural

centers of the Western

world.

Names

The Latin

Regnum Hungariae/Vngarie

(Regnum meaning kingdom); Regnum

Marianum (Kingdom of St.

Mary); or simply Hungaria was the form used in official

Latin documents from the beginning of the kingdom to the 1840s.

The German

name (Königreich Ungarn)

was used from 1849 to the 1860s, and the Hungarian

name (Magyar Királyság)

was used in the 1840s, and again from the 1860s to 1918. The names

in other languages of the kingdom were: Polish:

Królestwo Węgier,

Romanian:

Regatul Ungariei, Croatian:

Kraljevina Ugarska, Slovene:

Kraljevina Ogrska, Czech:

Uherské království,

Slovak:

Uhorské kráľovstvo,

Italian

(for the city of Fiume),

Regno d'Ungheria.

In Austria-Hungary

(18671918), the unofficial name Transleithania was

sometimes used to denote the regions covered by the Kingdom of

Hungary. Officially, the term Lands of the Holy Hungarian Crown

of Saint Stephen was included for the Hungarian part of the

Austro-Hungarian Empire, although this term was also in use prior

to that time.

History

From 9 BC to the end of the 4th century, Pannonia

was part of the Roman

Empire on a part of later Hungary's area. Among the first to

arrive were the Huns,

who built up a powerful empire under Attila

the Hun. After Hunnish rule faded away, the Germanic Ostrogoths

and then the Lombards

came to Pannonia, and the Gepids

had a presence in the eastern part of the Carpathian

Basin for about 100 years. In the 560s the Avars

founded the Avar

Khaganate,[5]

a state which maintained supremacy in the region for more than two

centuries and had the military power to launch attacks against all

its neighbours. The Avar rule ended when the Khaganate was

conquered by the Franks

under Charlemagne

in the West and the Bulgarians

under Krum

in the East. The Hungarians

led by Árpád

conquered the Carpathian

Basin in 895. They led several successful incursions

to Western Europe, until they were was stopped by Otto

I, Holy Roman Emperor in Battle

of Lechfeld. In the Carpathian Basin the Hungarians conquered

an existing Slavonic

state of Great

Moravia weakened after the death of king Svatopluk

I. The force led by Árpád is estimated to have consisted of

from about 400,000 to about 600,000 people,[6]

consisting of seven Hungarian tribes, one Kabar tribe, and other

smaller tribes.[7]

Their newly founded Principality

of Hungary (8961000) was the first documented Hungarian

state in the Carpathian

Basin.[8]

The

Medieval Kingdom (10001538)

Árpád

dynasty

The first kings of the kingdom were from the Árpád

dynasty, and the first Christian King

was Stephen

I of Hungary who was canonized

as a Catholic

saint.

He fought against Koppány

and in 998, with Bavarian

help, defeated him near Veszprém.

The Roman Catholic Church received powerful support from

Stephen I, who with Christian Hungarians

and German knights wanted a Christian kingdom established in Central

Europe. It was he who created the Hungarian heavy cavalry[clarification

needed] as an example for Western European

powers.

After his death, a period of revolts and conflict for supremacy

ensued between the royalty and the nobles. In 1051 armies of the Holy

Roman Empire tried to conquer Hungary,

but they were defeated at Vértes

mountain. The armies of the Holy Roman Empire continued to

suffer defeats; the second greatest battle was at the town now

called Bratislava,

in 1052. Before 1052 Peter Orseolo, a supporter of the Holy

Roman Empire, was overthrown by king Samuel

Aba of Hungary.[9][10]

This period of revolts ended during the reign of Béla

I. Hungarian chroniclers praised Béla

I for introducing new currency, such as the silver denarius,

and for his benevolence to the former followers of his nephew,

Solomon. The terms Nobilissimus

(most noble) and nobilissima familia (most noble family) have

been used since the 11th century for the King of Hungary and his

family, but it were then only a few that were mentioned in

official documents as such.

The second greatest Hungarian king, also from the Árpád

dynasty, was Ladislaus

I of Hungary, who stabilized and strengthened the kingdom. He

was also canonized as a saint. Under his rule Hungarians

successfully fought against the Cumans and conquered Croatia

in 1091, due to a dynastic crisis in Croatia, he managed to

swiftly seize power in the kingdom, he also was a claimant to the

throne due to the fact that his sister was married to the late

Croatian king Zvonimir.

Although it is still debated among historians, it is believed that

Ladislaus created a kind

of personal union between the two kingdoms. However kingship

over all of Croatia would not be achieved until the reign of his

successor Coloman.[11][12][13][14][15]

The provinces of Croatia and Slavonia, and after 1868 the

autonomous province of Croatia-Slavonia

had autonomy within the Kingdom of Hungary from 10911918.[11][12][16][17][18]

Also, one of the greatest Hungarian jurists and statesmen of the

16th century, István

Werbőczy in his work Tripartitum treats Croatia as

a kingdom separate to Hungary. In 1222 Andrew

II of Hungary issued the Golden

Bull which laid down the principles of law.

Mongol

invasion

In 1241, Hungary was invaded by the Mongols

and while the first minor battles with Subutai's vanguard probes

ended in seeming Hungarian victories, the Mongols finally

destroyed the combined Hungarian and Cuman armies at the Battle

of Mohi.

The Mongols attacked Hungary with three armies, one of them

through Poland in order to withhold possible Polish

auxiliaries, and defeated the army of Duke Henry

II the Pious of Silesia

at the Legnica.

A southern army attacked Transylvania

defeating the voivod

and crushing the Transylvanian Hungarian[citation

needed] army. The main army led by Batu

Khan and Subutai

attacked Hungary through the fortified Verecke

Pass and annihilated the army led by the count

Palatine on 12 March 1241.[19]

Despite the appearance of the Mongol invasion having been a

surprise attack, the Hungarians

had known, from various sources, that the Mongols

were coming. Notable heralds of the oncoming invasion include the Friar

Julian group, which warned the king about impending invasion

it had established contact with Magna

Hungaria and saw the aftermath of the destruction of both the

Magna Hungaria and Volga

Bulgaria earlier in the 13th century.

In 1242, after the end of the Mongol

invasion, numerous fortresses to defend against future

invasion were erected by Béla

IV of Hungary. In gratitude, the Hungarians

acclaimed him as the "Second Founder of the Homeland",

and the Hungarian Kingdom again became a considerable force in

Europe. In 1260 Béla

IV lost the War of Babenberg Succession, his army was defeated

at Battle

of Kressenbrunn by the united Czech troops, however after in

1278, Ladislaus

IV of Hungary and Austrian troops fully destroyed the Czech

army at Battle

on the Marchfeld.

In 1301, with the death of Andrew

III of Hungary, the Árpád dynasty died out. The dynasty was

replaced by the Angevins,

followed by the Jagiellonians,

and then by several non-dynastic rulers, notably Sigismund,

Holy Roman Emperor and Matthias

Corvinus.

The

Anjou Age

When Ladislaus IV of Hungary died before Andrew III, another

nobleman reclaimed the throne for himself: Charles

Martel of Anjou, the son of the King Charles

II of Naples and Mary

of Hungary (the daughter of the king Stephen

V of Hungary). However Andrew III assured the power for

himself, and ruled without inconvenience after the death of Charles

Martel in 1295. When Andrew III died in 1301 the queen Mary of

Hungary, who raised Charles Martel's children, reclaimed the

throne of Hungary for her grandson Charles

Robert of Anjou who was 13 years old. Taking control after a

chaotic period, he was finally crowned as the king Charles

I of Hungary. He implemented considerable economic reforms,

and defeated the remaining nobility who were in opposition to

royal rule, led by Máté

Csák. The kingdom of Hungary reached an Age of prosperity and

stability under the rule of the king who had already learned the

language from his grandmother, and also knew Italian, Latin, and

French. The gold mines of the Kingdom were extensively worked and

soon Hungary reached a prominent place in European gold

production. The Hungarian

forint currency was introduced to replace the denars, and soon

after the reforms introduced by the King, the economy of the

Kingdom was placed again in a correct direction after its

disastrous state in the 13th century.

Charles I exalted the cult to the King Saint Ladislaus

I of Hungary, and used him as a symbol of bravery, justice,

purity (actually this monarch was Knight, King and Saint,

everything at the same time, something unusual), being the ideal

to follow. Charles I also venerated his uncle Saint

Louis of Toulouse, and on the other hand he gave importance to

the cult of the princess Saint

Margaret of Hungary and Saint

Elisabeth of Hungary, which became an instrument for the new

king, added relevance to the lineage inheritance through the

feminine branches, legitimizing himself with it.[20]

Charles I restored the royal power which had fallen into feudal

lords' hands, and then he made them swear loyalty to himself, the

new nobility that stood by his side. For this he founded in 1326

the Order

of Saint George, which was the first secular chivalric

order in the world, and included the most important noblemen

of the Kingdom.

After marrying three times and losing all his wives one after

the other, he took as his fourth wife the daughter of the Polish

King Władysław

I the Elbow-high: Elisabeth

of Poland. She gave him many children, most of them boys,

which assured the continuity of the family in the power. When

Charles I died in 1342, his eldest son succeeded him and was

crowned as Louis

I of Hungary. The new King followed his father's steps, being

advised closely by his mother, making the widow queen one of the

most influential personalities in the Kingdom.

Before Charles I's death, he had also arranged the marriage of

his other sons, Andrew,

Duke of Calabria with the queen Joan

I of Naples. However, the Queen, fearing that a stranger might

take control over his throne (actually both belonged to the same

royal family), started conspiring and ordered Andrew's murder. The

prince was killed in 1345, and almost immediately the King Louis

declared war on Naples and conduced a first campaign in 1347-48.

However, the war was interrupted by the rage of the very

contagious Black

Death, and the Hungarian armies went back home. Surprisingly

the Italians suffered many deaths and the Hungarians were barely

affected (the wife of Louis I died of it). Without giving himself

up, the Hungarian King resumed the war in 1349-50, conquering the

Kingdom of Naples. Seeing that keeping rule in both far states, he

signed a treaty with the Queen Joan I and left them independent.

Decades later, Louis I met with success on the battlefield when he

defended the Hungarian Kingdom from new attacks by lesser Mongol

forces in the latter half of the 14th century.

Louis I's uncle died in 1370, and after this the King of

Hungary also inherited the Kingdom of Poland, because the monarch

had no children that could succeed him in the throne. In the

beginning Louis was not widely accepted as Polish king, and the

nobility protested. Even the Widow Queen Elisabeth of Poland was

threatened, and his committee was executed when she visited

Poland, because she was not considered as Polish by his people.

However, pacting with the nobility, Louis became the new king of

the two states. A tragic event occurred a decade later. In 1382

Louis died, leaving no male heirs for both kingdoms, only two

daughters: Mary

of Hungary and Saint Jadwiga

of Poland.

The

Sigismund Age

Louis

I of Hungary always kept good and close relationships with the

Holy

Roman Emperor Charles

IV of Luxembourg. Louis considered Charles's son Sigismund

of Luxembourg to succeed him as King of Hungary. He named him

his heir and arranged the marriage with his daughter Mary

of Hungary. Sigismund lived in the court of Louis, and soon

learned the language and Hungarian way of life. However, the queen

consort Elizabeth

of Bosnia, mother of Mary and Jadwiga disliked the very young

prince's presence. After the death of Louis, the widowed Queen

made her best effort for Sigismund not to be crowned as King of

Hungary. This generated a chaotic period during which the little

Mary became queen of Hungary as her mother and the nobility

decided for her. Sigismund and Mary were married in 1385, but soon

he was sent away.

The Hungarian noblemen brought forth the King of Naples, Charles

of Anjou-Durazzo, who was the only living male relative to

Louis I of Hungary, and crowned him as Charles II of Hungary

in 1385. However, the Widow Queen and her advisors soon conspired

to regain power and Charles II was murdered in 1386. The enraged

people created disturbances, and the Widow Queen and Mary lost a

lot of adepts, They were eventually were captured and locked up in

a tower. The Widow Queen was strangled in 1387, and soon Mary was

released by Sigismund, who was crowned king of Hungary, having the

full support of the nobility.

Sigismund became a strong king who created many improvements in

the Hungarian law system and who rebuilt the palaces of Buda and

Visegrád. He brought materials from Austria and Bohemia and

ordered the creation of the most luxurious building in all central

Europe. In his laws can be seen the traces of the early mercantilism.

He worked hard to keep the nobility under his control.

A great part of his reign was dedicated to the fight with the

Ottoman empire, which started to extend its frontiers and

influence to Europe. In 1396 was fought the Battle

of Nicopolis against the Ottomans, which resulted in a defeat

for the Hungarian-French forces led by Sigismund and Philip

of Artois, Count of Eu. However, Sigismund continued to

successfully contain the Ottoman forces outside of the Kingdom for

the rest of his life.

Losing popularity among the Hungarian nobility, Sigismund soon

became victim of an attempt against his rule, and Ladislaus

of Anjou-Durazzo (the son of the murdered King of Naples

Charles II of Hungary) was called in and crowned. Since the

ceremony was not performed with the Hungarian Holy Crown, and in

the city of Székesfehérvár, it was considered illegitimate.

Ladislaus stayed only few days in Hungarian territory and soon

left it, no longer an inconvenience for Sigismund.

In 1408 he founded the Order

of the Dragon, which included the most of the relevant

monarchs and noblemen of that region of Europe in that time. This

was just a first step for what was coming. In 1410 he was elected King

of the Romans, making him the supreme monarch over the German

territories. He had to deal with the Hussite

movement, a religious reformist group that was born in Bohemia,

and he presided at the Council

of Constance, where the theologist founder Jan

Hus, was judged. In 1419 Sigismund inherited the Crown

of Bohemia after the death of his brother Wenceslaus

of Luxembourg, obtaining the formal control of three medieval

states, but he struggled for control of Bohemia until the peace

agreement with the Hussites and his coronation in 1436. In 1433

was crowned as Holy Roman Emperor by the Pope and ruled until his

death in 1437, leaving as his only heir his daughter Elizabeth

of Luxembourg and her husband. The marriage of Elizabeth was

arranged with the Duke Albert

V of Austria, who was later crowned as King Albert of

Hungary in 1437.

Hunyadi

family

The Hungarian kingdom's golden age was during the reign of Matthias

Corvinus, the son of John

Hunyadi. His nickname was "Matthias the Just". He

further improved the Hungarian economy and practised astute

diplomacy in place of military action whenever possible. Matthias

did undertake campaigning when necessary. In 1485, aiming to limit

the influence and meddling of the Holy Roman Empire in Hungary's

affairs, he occupied Vienna for 5 years. After his death, Vladislaus

II of Hungary of the Jagiellonians

was placed on the Hungarian throne.

At the time of the initial Ottoman encroachment, the Hungarians

successfully resisted conquest. John

Hunyadi was leader of the Long

Campaign in which the Hungarians

tried to expel the Turks from the Balkans. Initially, it was

successful, but finally they had to withdraw. In 1456 John

Hunyadi, the father of Matthias Corvinus, delivered a crushing

defeat on the Ottomans at the Siege

of Belgrade. The Noon

bell commemorates the fallen Christian warriors. In the 15th

century, the Black

Army of Hungary was a formidable modern mercenary army with

the Hussars

the most skilled troops of the Hungarian

cavalry. In 1479, under the leadership of Pál

Kinizsi, the Hungarian army destroyed the Ottoman and

Wallachian troops at the Battle

of Breadfield. The Army of Hungary destroyed its enemies

almost every time when Matthias was the king.

In 1526, at the Battle

of Mohács, the forces of the Ottoman

Empire annihilated the Hungarian army. In trying to escape Louis

II of Hungary drowned in the Csele Creek. The leader of the

Hungarian army, Pál

Tomori, also died in the battle.

Kingdom

of Hungary between 1538 and 1867

The

divided kingdom

Due to Ottoman pressure, central authority collapsed and a

struggle for power broke out. The majority of Hungary's ruling

elite elected János

Szapolyai (10 November 1526). A small minority of aristocrats

sided with Ferdinand

I, Holy Roman Emperor, who was Archduke of Austria,

and was related to Louis by marriage. Due to previous agreements

that the Habsburgs

would take the Hungarian throne if Louis died without heirs,

Ferdinand was elected king by a rump diet

in December 1526. The kingdom was divided between Szapolyai and

Ferninand I in 1538, according to the secret agreement of Nagyvárad.[21]

Although the borders shifted frequently during this period, the

three parts can be identified, more or less, as follows:

- Royal

Hungary, which consisted of northern and western

territories where Ferdinand I was recognized as king of

Hungary. This part is viewed as defining the continuity of the

Kingdom of Hungary. The territory along with Ottoman Hungary

suffered greatly from the nearly constant wars taking place.

- Ottoman

Hungary The Great

Alföld (i.e. most of present-day Hungary, including

south-eastern Transdanubia and the Banat),

partly without north-eastern present-day Hungary.

- Eastern

Hungarian Kingdom under the Szapolyai.

Note that this territory, often under Ottoman influence, was

different from Transylvania proper and included various other

territories sometimes referred to as Partium.

Later the entity was called Principality

of Transylvania.

On 29 February 1528, King John

I of Hungary received the support of the Ottoman Sultan. A

three-sided conflict ensued as Ferdinand moved to assert his rule

over as much of the Hungarian kingdom as he could. By 1529 the

kingdom had been split into two parts: Habsburg Hungary and the

"eastern-Kingdom of Hungary". At this time there were no

Ottomans on Hungarian territories, except Srem's important

castles. In 1532, Nikola

Juriić defended Kőszeg

and stopped a powerful Ottoman army. By 1541, the fall of Buda

marked a further division of Hungary into three areas. In the year

1542 Petar

Keglević the ban

of Croatia

and Slavonia

from 1537 to 1542 was sentenced as an infidel

by the Parliament in Bratislava,

because of his special agreement with the Ottoman

Empire. Even with a decisive 1552 victory over the Ottomans at

the Siege

of Eger, which raised the hopes of the Hungarians,

the country remained divided until the end of the 17th century.

The heroes' memory continues to live in a famous poem written by Sebestyén

Tinódi Lantos, Summáját írom Eger várának

("I am writing the history of Eger's castle"). Transylvania

evolved during the following centuries into a distinctive

autonomous unit within the Hungarian kingdom, with its special

voivode (or governor), its united, although heterogeneous,

leadership (descended from Szekler,

Saxon,

and Magyar

colonists), and its own constitution[22]

until 1526

when it effectively became independent[22]

In the following centuries there were numerous attempts to push

back the Ottoman

forces, such as the Long

War or Thirteen Years' War (29 July 1593 - 1604/11 November

1606) led by a coalition of Christian forces. In 1644 the Winter

Campaign by Miklós

Zrínyi burnt the crucial Suleiman Bridge of Osijek

in eastern Slavonia,

interrupting a Turkish supply line in Hungary.

At the Battle

of Saint Gotthard (1664), Austrians

and Hungarians

defeated the Turkish army.

After the Ottoman invasion of Austria failed in 1683, the

Habsburgs went on the offensive against the Turks. By the end of

the 17th century, they managed to conquer the remainder of the

historical Kingdom of Hungary and the principality of

Transylvania. For a while in 1686, the capital Buda

was again free, with European help.

The

Kuruc age

Rákóczi's War for Independence (17031711) was the first

significant freedom fight in Hungary against absolutist Habsburg

rule. It was fought by a group of noblemen, wealthy and

high-ranking progressives who wanted to put an end to the

inequality of power relations, led by Francis II Rákóczi (II. Rákóczi

Ferenc in Hungarian). Its main aims were to protect the rights of

the different social orders, and to ensure the economic and social

development of the country. Due to the adverse balance of forces,

the political situation in Europe and internal conflicts the

freedom fight was eventually suppressed, but it succeeded in

keeping Hungary from becoming an integral part of the Habsburg

Empire, and its constitution was kept, even though it was only a

formality.

After the departure of the Ottomans, the Habsburgs dominated

the Hungarian Kingdom. The Hungarians' renewed desire for freedom

led to Rákóczi's

War for Independence. The most important reasons of the war

were the new and higher taxes and a renewed Protestant movement. Rákóczi

was a Hungarian nobleman, son of the legendary heroine Ilona

Zrínyi. He spent a part of his youth in Austrian

captivity. The Kurucs were troops of Rákóczi. Initially,

the Kuruc

army attained several important victories due to their superior

light cavalry. Their weapons were mostly pistols, light sabre and fokos.

At the Battle

of Saint Gotthard (1705), János

Bottyán decisively defeated the Austrian army. The famous

Hungarian colonel Ádám

Balogh nearly captured Joseph

I, the King of Hungary and Emperor of Austria.

In 1708, the Habsburgs finally defeated the main Hungarian army

at Battle

of Trencsén, and this diminished the further effectiveness of

the Kuruc army. While the Hungarians

were exhausted by the fights, the Austrians

defeated the French army in the War

of the Spanish Succession. They could send more troops to Hungary

against the rebels. Transylvania became part of Hungary

again starting at the end of the 17th century, and was led by

governors.[23][24]

Age

of Enlightenment

In 1711, Austrian Emperor Charles

VI became the next ruler of Hungary. From this time on, the

designation Royal Hungary was abandoned, and the area was

once again referred to as the Kingdom of Hungary.[citation

needed] Throughout the 18th century, the

Kingdom of Hungary had its own Diet (parliament) and constitution,

but the members of the Governor's Council (Helytartótanács,

the office of the palatine)

were appointed by the Habsburg monarch, and the superior economic

institution, the Hungarian

Chamber, was directly subordinated to the Court

Chamber in Vienna.

The Hungarian Language reform started under reign of Joseph

II. The reform age of Hungary was started by István

Széchenyi a Hungarian noble, who built one of the greatest

bridges of Hungary, the Széchenyi

Chain Bridge. The official

language remained Latin

until 1844. Then, between 1844 and 1849, and from 1867, Hungarian

became the official language.

Hungarian

Revolution of 1848

The European revolutions of 1848 swept Hungary, as well. The

Hungarian Revolution of 1848 sought to redress the long suppressed

desire for political change, namely independence. The Hungarian

National Guard was created by young Hungarian patriots in 1848. In

literature, this was best expressed by the greatest poet of the

revolution, Sándor

Petőfi.

As war broke out with Austria, Hungarian military successes,

which included the brilliant campaigns of the great Hungarian

general, Artúr

Görgey, forced the Austrians on the defensive. One of the

most famous battles of the revolution, the Battle

of Pákozd, was fought on the 29 September 1848, when the

Hungarian revolutionary army led by Lieutenant-General János Móga

defeated the troops of the Croatian Ban Josip

Jelačić. Fearing defeat, the Austrians pleaded for

Russian help, which, combined with Austrian forces, quelled the

revolution. The desired political changes of 1848 were again

suppressed until Austro-Hungarian

Compromise of 1867.

Austria-Hungary

(18671918)

Following the Austro-Hungarian

Compromise of 1867, the Habsburg Empire became the "dual

monarchy" of Austria-Hungary.

The Austro-Hungarian economy changed dramatically during the

existence of the Dual Monarchy. Technological change accelerated

industrialization and urbanization. The capitalist way of

production spread throughout the Empire during its fifty-year

existence and obsolete medieval institutions continued to

disappear. By the early 20th century, most of the Empire began to

experience rapid economic growth. The GNP per capita grew roughly

1.45% per year from 1870 to 1913. That level of growth compared

very favorably to that of other European nations such as Britain

(1.00%), France (1.06%), and Germany (1.51%).

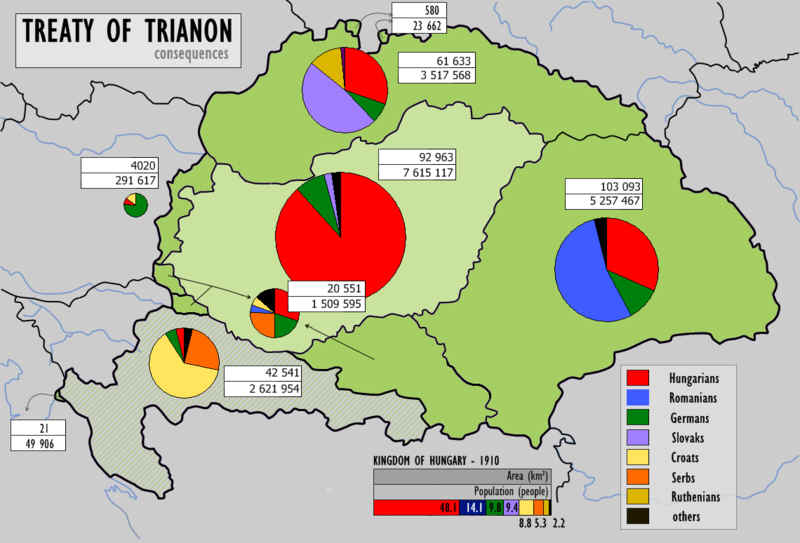

Treaty

of Trianon set in 1920

The new borders set in 1920 by the Treaty

of Trianon ceded 72% of the historically Hungarian territory

of the Kingdom of Hungary to the neighbouring states. The

beneficiaries were Romania,

the newly formed states of Czechoslovakia,

and the Kingdom

of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. This left more than 3.5 million

ethnic Hungarians

outside the new borders. Many view this as contrary to the terms

laid out by US President Woodrow

Wilson's Fourteen

Points, which were intended to honour the ethnic makeup of the

territories.

See also

Web Links

|

Kingdom of Hungary ("Ungarn")

within Austria-Hungary, 1899. |

|

|

Hungary (including Croatia)

in 1190, during the rule of Béla

III (orange) |

|

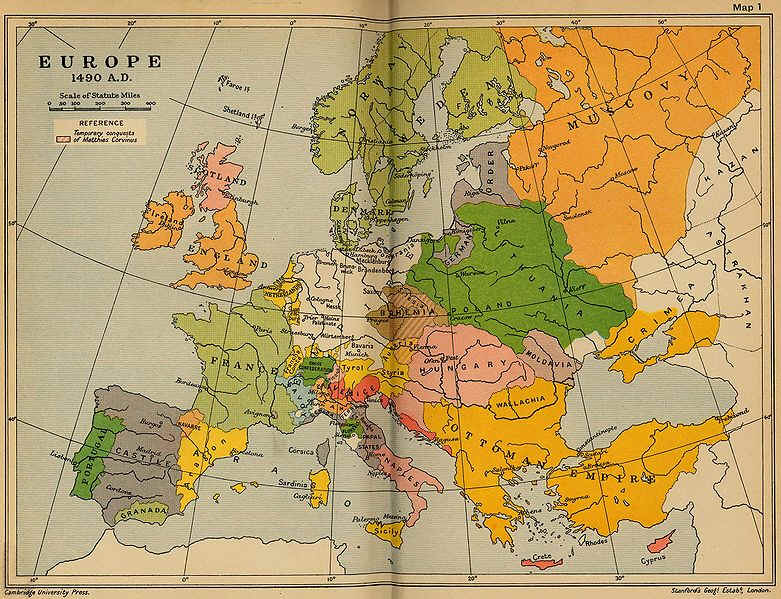

| Hungary

in 1490 |

|

|

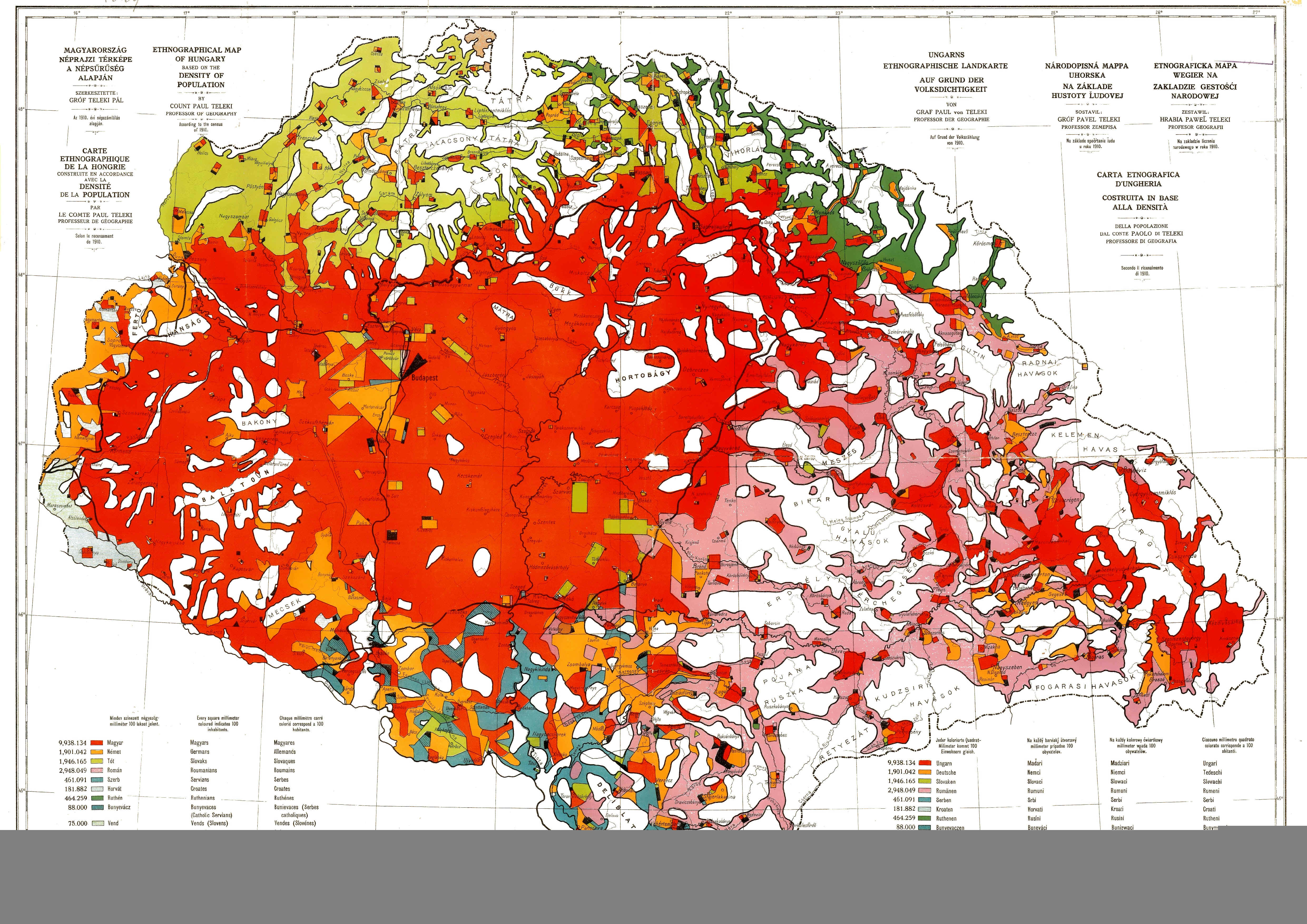

Ethnographic map of Hungary without Croatia

and Slavonia (1910). The population of areas under 20

persons/km2 is represented in the nearest area

above that level, and the area is left blank. |

|

|

The Treaty

of Trianon: Hungary lost 72% of its territory, and lost

its sea ports in Croatia. 3,425,000 ethnic Hungarians found

themselves separated from their motherland. Hungary lost

half of its 10 biggest cities and all of its precious metal

mines |

|

| |

|

|

| The Magyars

A Thousand Years of

Hungary

http://hungarianhistory.freeservers.com/magyars.html |

Magyar

Origins

When the

Magyar people entered the land of Europe, they seemed a part of

the Turkic hordes roaming between South-Eastern Europe and

Central Asia. Greater evidence points to Asia as the Magyar's

original homeland. Exactly what part of Asia has been a matter

of dispute for generations, but it is clear that the Magyars

came from the East. The horse was the most important animal to

the Magyars. They both traveled and fought on horseback during

their long migrations from the east and eventually into what is

present day Hungary. Their weapons and style of fighting were

identical with those of the Huns, Avars and other mounted

nomadic peoples. But the Magyars were a distinct group separate

from the Huns, Avars and Turks.

Finno-Ugrian

Theory

The most

widely accepted theory of the Magyar's origin is the

Finno-Ugrian concept. Advocates of this theory believe the

linguistic and ethnic kinship between the Hungarians and the

Finns, Esthonians, Ostyaks and Voguls provide evidence for the

origin of the Magyars. This relation of the Magyars with the

Finns places the ancient homeland of the Finno-Ugrians on both

sides of the southern Ural Mountains. The advocates of this

theory insist that Magyars came from this group in the Urals,

and as the theory explains, it was about 2000 B.C. that the

Finnish branch broke away to settle in the Baltic area. The

Magyars remained on the West Siberian steppes with the other

Ugrian peoples until 500 B.C. It was then that the Magyars

crossed the Urals westward to settle in what is present day

Soviet Bashkiria, north of the Black Sea and the Caucasus. The

Magyars remained here for centuries with the various Ural-Altaic

peoples such as the Huns, Turkic Bulgars, Alans and Onogurs. The

Magyars soon adopted many cultural traits and customs of these

people and it was from the region of Soviet Bashkiria that the

Magyars started their migration westward toward the Carpathians.

After

World War II, the Finno-Ugrian theory was challenged by scholars

who argued that the Finno-Ugrian theory was based on linguistics

alone, without support in anthropology, archeology or written

records.

Orientalist

Theory

Scholars

known as orientalists believe that the origin of Magyars and

their language is not found in the Urals, but in Central Asia

known as the Turanian Plain or Soviet Turkestan which stretches

from the Caspian Sea eastward to Lake Balchas. Ancient history

has traditionally called this region Scythia. Folklore holds

that the Magyars are related to the Scythians who built the

great empire of the 5th century B.C. After the Scythian empire

dissolved, the Turanian Plain witnessed the rise and fall of

empires built between the first and ninth centuries A.D. by the

Huns, Avars, Khazars and various Turkic peoples, including the

Uygurs. The Magyars subsequently absorbed much of the culture

and tradition of these peoples and many Onogur, Sabir, Turkic,

and Ugrian people were assimilated with the Magyars, resulting

in the Magyar amalgam, which entered the Carpathian Basin in the

later half of the ninth century A.D.

Scholars

of Far Eastern history believe that the Magyars were also

exposed to the Sumerian culture in the Turanian Plain. Linguists

of the 19th century, including Henry C. Rawlinson, Jules Oppert,

Eduard Sayous and Francois Lenormant found that knowledge of the

Ural-Altaic languages such as Magyar, helps to decipher Sumerian

writings. Cunei form writing was found to be used by the Magyars

long before they entered the Carpathian Basin. The similarity of

the two languages has led orientalists to form a

Sumerian-Hungarian connection. The orientalists speculate that a

reverse of the Finno-Ugrian theory may be possible. The theory

holds that if the proto-Magyars were neighbors of the

proto-Sumerians in the Turanian Plain, then the evolution of the

Hungarian language must have been a result of Sumerian rather

than Finno-Ugrian influences. The theory in turn holds that

rather than being the recipients of a Finno-Ugrian language, it

was the Magyars who imparted their language to the Finns and

Estonians without being ethnically related to them. What

scholars site for added evidence for this theory is the fact

that the Magyars have always been numerically stronger than

their Finno-Ugrian neighbors combined. The theory believes that

the Finns and Ugors received linguistic strains from a Magyar

branch who had broken away from the main body on the Turanian

Plan, and migrated to West Siberia.

The

Magyar-Uygur Theory

The

connection between the Magyars and the Uygurs tie Hungarians

even closer to Asia. The Uygurs are people who live in the

Xinjiang province of China. The Uygurs are Caucasian in

appearance and maintain a Turkic language. To the north of the

Uygar's border stretches the Dzungarian Basin which has a

striking similarity to the word Hungarian. Northeast of the

Dzungaria lies the Altai Mountain Range, a name used by

linguists to define the Ural-Altaic language group to which the

Magyar language belongs. Further up to the north stretches the

Lake Baykal region where first the Scythians, then the Huns

emerged to conquer the Turanian Plain. The Magyars, Uygurs and

the Turks may also have started their migrations from the

northeastern part of the Baykal area.

Further

anthropological, archeological and linguistic research must be

conducted on this theory, but is limited by the little access

the Chinese government grants foreigners to the region. There

are, however, many Asiatic influences seen among Hungarians

today. Hungarian legends and folk tales are strikingly similar

to those of Asian peoples. The structure of Magyar folk music,

which uses the pentatonic scale, also points to Asian origins.

The beautiful gates of the Székely people in Transylvania bear

a strong resemblance to those in the pagodas of China. The

ornate tombstones carved from wood are also similar to those

seen in Chinese cemeteries. The Hungarian cuisine shows traces

of Asia in its use of strong spices such as paprika, pepper,

saffron, and ginger.

The

Hun-Avar Theory

Much of this

theory has been perpetuated by folk tale. Most Hungarians today

can tell the story of the Legend of the White Stag. The story

describes how two sons of Nimrod, Hunor and Magor, were lured

for days into a new land by a fleeing white stag. The stag

suddenly vanishes without trace. But the disappointed young

hunters hear laughing and singing. The two dismount and follow

the laughing until they come across a lake in which two

beautiful maidens are splashing. The two hunters take the

maidens as wives. The Huns are Hunor's descendent, and the

Magyars are Magor's descendents. There are variations on the

folk tale including Simon Kézai's version in his 1283

chronicle, Gesta Hungarorum. The same mythical tale takes on a

slightly somber and more realistic approach. Hunor and Magor are

Chief Ménrót's grown up sons who had reached maturity and had

moved into a separate tent. "One day it happened that, as

they were going out to hunt, a hind suddenly appeared in front

of them on the plains, and as they undertook to pursue her, she

fled from them into the Maeotian marshes. Since she completely

disappeared there from their eyes, they searched for her a long

time but could not chance upon her traces. After having

traversed the said marshes, they decided the marshes were

suitable for raising livestock. They returned to their father,

and securing his consent, they moved into the Maeotian marshes

with all their animals to settle down there. The region of

Maeotis is a neighbor of Persia. Apart from a very narrow wading

place, it is enclosed by the sea everywhere. It has absolutely

no streams, but it teems with grass, trees, fish, fowl, and

game. Access to and exit from it is difficult. Thus settling in

the Maeotian marshes, Hunor and Magor did not move from there

for five years. In the sixth year they wandered out, and by

chance they came upon the wives and children of Belárs sons,

who stayed at home without their men folk. Quickly galloping off

with them and their belongings, they carried them off into the

Maeotian marshes. It so happened that among the children they

also seized the two daughters of Dula, the Prince of the Alans.

Hunor married one and Magor the other. All the Huns descend from

these women."

From Hunor

came the great and dreaded leader Attila. After the kingdom of

Attila fell apart shortly after his death, further waves of

people moved in to the Carpathian Basin but all were crushed by

the Avars, a quickly emerging branch of the Ural-Altaic group.

The Avars founded and empire on top of what used to be

Attila's-the region between the Danube and the Tisza rivers. The

Avars even used a weapon perfected by the Huns, the curved sabre

gladicus hunnicus. The Avars downfall, however, was hastened by

the development of Charlemagne's Frankish Empire. The Avars and

Charlemagne's army went to battle from 796 to 803 A.D. The Avars

were finally defeated by the Frankish troops and most Avar

tribes returned to the slopes of the Caucasian Mountains. Others

stayed and mingled with the Slavs of the area and later with the

Magyars. When the Magyar tribes arrived under Árpád, they

found a sparse population including many Avars. According to the

Teri-i-Üngürüsz chronicle, "When they arrived in the

land, they saw its many rivers teeming with fish, the land rich

in fruits and vegetables, and members of other tribes, some of

whom understood their language."

This

theory of Hun-Avar-Magyar progression into the Carpathian Basin,

however, is only part of the story.

Black

and White Magyars

The Chinese

believed that there were five cardinal directions, the fifth

being "the center of the universe", China itself. Each

of the five directions was symbolized by a color. The central

point, China, was indicated by yellow, for the gold that befit

His Imperial Highness. The North, shrouded in dark Arctic

nights, was black. The West was designated as white, a color

that reflected the blinding white sands of the vast deserts on

the western horizon. Red represented the sun of the South, and

the East was symbolized by blue, the color of the ocean

eternally washing China's eastern shores.

Based on

these color symbols, the White Magyars (or White Ugurs)

represented the Western branch of their race. According to

ancient Russian chronicles, the White Magyars appeared in the

Carpathian Basin as early as 670-680 A.D., first with the

Bulgars, and later with the Avars. The second branch of Magyar

tribes-called Black Magyars in ancient Russian chronicles-took a

different route. The directions of that route are still debated

by Finno-Ugrian and orientalist theorists, but the end result

was that the Black Magyars became connected with peoples

belonging to the Ural-Altaic groups. These included a range of

peoples from Manchuria to Turkey.

Among

these groups the Finno-Ugrian/Magyars drew closest to the Turks,

who were warriors with a talent for statecraft. This association

with the Turks created a new blend of Magyar: Finno-Ugrian in

language but Ural-Altaic in culture. This was the strain of

Magyars that in 895 A.D. would ride into the Carpathian Basin

under Árpád-following the footsteps of the White Magyars who

appeared in the Carpathian Basin in the 670s A.D. Árpád's

Magyars has been termed by some modern historians as the second

wave in a two-phased conquest of the Hungarian homeland. Whether

this theory is correct or not, it seems fairly certain that the

Szeklers (székelyek) had been long-time inhabitants of

Transylvania before the Magyars arrived.

Sources:

István Lázár, "Hungary: A Brief History" Corvina

Books, Budapest: 1990, pp. 11-35.

Stephen Sisa, "The Spirit of Hungary" Vista Books, New

Jersey: 1995, pp 1-6.

|

| |

|

|