|

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_South_Carolina#18th_century

|

Colonial

period

Main

article: Colonial

period of South Carolina

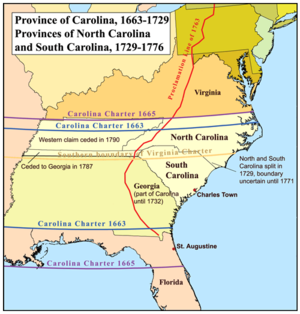

The

Carolina Colonies

By

the end of the 16th century, the Spanish and French had left the

area of South

Carolina after several reconnaissance missions, expeditions

and failed colonization

attempts, notably the French outpost of Charlesfort

followed by the Spanish mission of Santa

Elena on modern-day Parris

Island between 1562 and 1587. In 1629, Charles

I, King of England,

granted his attorney general a charter to everything between

latitudes 36 and 31. He called this land the Province of Carlana,

which would later be changed to "Carolina" for

pronunciation, after the Latin

form of his own name.

In

1663, Charles

II gave the land to eight nobles, the Lords

Proprietors, who ruled the Province

of Carolina as a proprietary colony. After the Yamasee

War of 1715-1717, the Lords Proprietors came under increasing

pressure and were forced to relinquish their charter to the Crown

in 1719. The proprietors retained their right to the land until

1719, when the colony was officially split into the provinces of North

Carolina and South

Carolina, crown colonies.

In

April 1670 settlers arrived at Albemarle Point, at the confluence

of the Ashley

and Cooper

rivers. They founded Charles

Town, named in honor of King Charles II. Throughout the Colonial

Period, the Carolinas participated in many wars against the

Spanish and the Native

Americans, including the Yamasee

and Cherokee

tribes. In its first decades, the colony's

plantations were relatively small and its wealth came from Indian

trade, mainly in Indian

slaves and deerskins.

The slave trade affected tribes throughout the Southeast, and

historians estimate that Carolinians exported 24,000-51,000 Indian

slaves from 1670–1717, sending them to markets ranging from Boston

to the Barbados.[6]

Planters financed the purchase of African

slaves by their sale of Indians.

18th

century

In

the 1700-1770 era, the colony possessed many advantages -

entrepreneurial planters and businessmen, a major harbor, the

expansion of cost-efficient African slave labor, and an attractive

physical environment, with rich soil and a long growing season,

albeit with endemic malaria.

It became one of the wealthiest of the British colonies. Rich

colonials became avid consumers of services from outside the

colony, such as mercantile services, medical education, and legal

training in England. Almost everyone in 18th-century South

Carolina felt the pressures, constraints, and opportunities

associated with the growing importance of trade.[7]

Yemasee

war

A

pan-Indian alliance rose up against the settlers in the Yamasee

War (1715–1717) and nearly destroyed the colony. But the

Yemasee were defeated and, with exposure to European infectious

diseases, the backcountry's Yemasee population was greatly

reduced.[8]

Slaves

After

the Yamasee war, the planters turned exclusively to importing

African slaves for labor. They used their labor to create rice and

indigo

plantations as commodity crops. Building dams, irrigation ditches

and related infrastructure, enslaved Africans created the

equivalent of huge earthworks

to regulate water for the rice culture.

Most

of the slaves originated in West Africa, and in the lowlands and

on the Sea Islands, where large populations of Africans lived

together, they developed a creolized culture and language known as

Gullah/Geechee (the latter a term used in Georgia). They

interacted with and adopted some elements of the English language

and colonial culture and language. The Gullah adapted to multiple

factors in American society during the slavery years. Since the

nineteenth century, they have marketed or otherwise used their

distinctive lifeways, products, and language to perpetuate their

unique ethnic and racial identity.[9]

Low

Country

The

Low

Country was settled first, dominated by wealthy English men

who became owners of large amounts of land on which they created plantations.[10]

They first transported white indentured

servants as laborers, mostly teenage youth from England who came

to work off their passage in hopes of learning to farm and buying

their own land. Planters also imported African laborers to the

colony. In the early colonial years, social boundaries were fluid

between indentured laborers and slaves, and there was considerable

intermarriage. Gradually the terms of enslavement became more

rigid and slavery became a racial caste. With a decrease in

English settlers as the economy improved in England before the

beginning of the 18th century, the planters began to rely chiefly

on enslaved Africans for labor.

The

market for land functioned efficiently and reflected both rapid

economic development and widespread optimism regarding future

economic growth. The frequency and turnover rate for land sales

were tied to the general business cycle; the overall trend was

upward, with almost half of the sales occurring in the decade

before the American Revolution. Prices also rose over time,

parallel with the rise in the price for rice. Prices dropped

dramatically, however, in the years just before the war, when

fears arose about future prospects outside the system of English

mercantilist trade.[11]

Back

country

In

contrast to the Tidewater, the back country was settled later,

chiefly by Scots-Irish

and North British migrants, who had quickly moved down from Pennsylvania

and Virginia.

The immigrants from Ulster, the Scottish lowlands and the north of

England (the border counties) comprised the largest group from the

British Isles before the Revolution. They came mostly in the 18th

century, later than other colonial immigrants. Such "North

Britons were a large majority in much of the South Carolina

upcountry." The character of this environment was "well

matched to the culture of the British borderlands."[12]

They settled in the backcountry throughout the South and relied on

subsistence farming. Mostly they did not own slaves. Given the

differences in background, class, slaveholding, economics and

culture, there was longstanding competition between the Low

Country and Upcountry that played out in politics.

Rice

Planters

earned wealth from two major crops: rice and indigo,

both of which relied on cultivation by slave labor.[13]

Historians no longer believe that the blacks brought the art of

rice cultivation from Africa.[10]

Exports of these crops led South Carolina to become one of the

wealthiest colonies prior to the Revolution. Near the beginning of

the 18th century, planters began rice culture along the coast,

mainly in the Georgetown and Charleston areas. The rice became

known as Carolina Gold, both for its color and its ability to

produce great fortunes for plantation owners.[14]

Indigo

In

the 1740s, Eliza

Lucas Pinckney began indigo culture and processing in coastal

South Carolina. Indigo was in heavy demand in Europe for making

dyes for clothing. An "Indigo Bonanza" followed, with

South Carolina production approaching a million pounds (400 plus

Tonnes) in the late 1750s. This growth was stimulated by a British

bounty of six pence per pound.[15]

South Carolina did not have a monopoly of the British market, but

the demand was strong and many planters switched to the new crop

when the price of rice fell. Carolina indigo had a mediocre

reputation because Carolina planters failed to achieve consistent

high quality production standards. Carolina indigo nevertheless

succeeded in displacing French and Spanish indigo in the British

and in some continental markets, reflecting the demand for cheap

dyestuffs from manufacturers of low-cost textiles, the

fastest-growing sectors of the European textile industries at the

onset of industrialization.[16]

In

addition, the colonial economy depended on sales

of pelts (primarily deerskins), and naval stores and timber.

Coastal towns began shipbuilding to support their trade, using the

prime timbers of the live

oak.

Revolutionary

War

John

Rutledge had many roles in South Carolina's history throughout the

American Revolution.

Main

article: South

Carolina during the American Revolution

Prior

to the American

Revolution, the British

began taxing American colonies to raise revenue.

Residents of South Carolina were outraged by the Townsend Acts

that taxed tea, paper, wine, glass, and oil. To protest the Stamp

Act, South Carolina sent the wealthy rice planter Thomas

Lynch, twenty-six-year-old lawyer John

Rutledge, and Christopher

Gadsden to the Stamp

Act Congress, held in 1765 in New York. Other taxes were

removed, but tea taxes remained. Soon residents of South Carolina,

like those of the Boston

Tea Party, began to dump tea into the Charleston Harbor,

followed by boycotts

and protests.

South

Carolina set up its state government and constitution on March 26,

1776. Because of the colony's longstanding trade ties with Great

Britain, the Low Country cities had numerous Loyalists. Many of

the Patriot battles fought in South Carolina during the American

Revolution were against loyalist

Carolinians and the Cherokee

Nation, which was allied with the British. This was to British

General Henry

Clinton's advantage, as his strategy was to march his troops

north from St.

Augustine and sandwich George

Washington in the North. Clinton alienated Loyalists and

enraged Patriots

by attacking and nearly annihilating

a fleeing army of Patriot soldiers who posed no threat.

White

colonists were not the only ones with a desire for freedom.

Estimates are that about 25,000 slaves escaped, migrated or died

during the disruption of the war, 30 percent of the state's slave

population. About 13,000 joined the British, who had promised them

freedom if they left rebel masters and fought with them. From 1770

to 1790, the proportion of the state's population made up of

blacks (almost all of whom were enslaved), dropped from 60.5

percent to 43.8 percent.[18]

On

October 7, 1780, at Kings

Mountain, John Sevier and William Campbell, assaulted the

'high heel' of the wooded mountain, the smallest area but highest

point, while the other seven groups, led by Colonels Shelby,

Williams, Lacey, Cleveland, Hambright, Winston and McDowell

attacked the main Loyalist position by surrounding the 'ball' base

beside the 'heel' crest of the mountain. North and South

Carolinians attacked the British Major Patrick

Ferguson and his body of Loyalists on a hilltop. This was a

major victory for the Patriots, especially because it was won by militiamen

and not trained Continentals. Thomas Jefferson called it,

"The turn of the tide of success."[19]

It was the first Patriot victory since the British had taken

Charleston.

While

tensions mounted between the Crown and the Carolinas, some key

southern Pastors became a target of King George: "...this

church (Bullock Creek) was noted as one of the "Four

Bees" in King George's bonnet due to its pastor, Rev. Joseph

Alexander, preaching open rebellion to the British Crown in June

1780. Bullock Creek Presbyterian Church was a place noted for

being a Whig party stronghold. Under a ground swell of such Calvin

protestant leadership, South Carolina moved from a back seat to

the front in the war against tyranny. Patriots went on to regain

control of Charleston

and South Carolina with untrained militiamen by trapping Colonel Banastre

"No Quarter" Tarleton's troops along a river.

In

1787, John

Rutledge, Charles

Pinckney, Charles

Cotesworth Pinckney, and Pierce

Butler went to Philadelphia where the Constitutional

Convention was being held and constructed what served as a

detailed outline for the U.S.

Constitution. The federal Constitution was ratified by the

state in 1787. The new state constitution was ratified in 1790

without the support of the Upcountry.

Scots

Irish

During

the American

Revolution, the Scots Irish in the back country in most states

were noted as strong patriots. One exception was the Waxhaw

settlement on the lower Catawba

River along the North Carolina-South Carolina boundary, where Loyalism

was strong. The area had two main settlement periods of Scotch

Irish. During the 1750s-1760s, second- and third-generation Scotch

Irish Americans moved from Pennsylvania, Virginia, and North

Carolina. This particular group had large families, and as a group

they produced goods for themselves and for others. They generally

were patriots.

Just

prior to the Revolution, a second stream of immigrants came

directly from northern Ireland via Charleston. Mostly poor, this

group settled in an underdeveloped area because they could not

afford expensive land. Most of this group remained loyal to the

Crown or neutral when the war began. Prior to Charles

Cornwallis's march into the backcountry in 1780, two-thirds of

the men among the Waxhaw settlement had declined to serve in the

army. British victory at the Battle of the Waxhaws resulted in

anti-British sentiment in a bitterly divided region. While many

individuals chose to take up arms against the British, the British

forced the people to choose sides, as they were trying to recruit

Loyalists for a militia.[20]

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_South_Carolina#18th_century

|