|

Arkansas Territorial Militia

| http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arkansas_Territorial_Militia#Arkansas_Territory |

|

Arkansas Territorial Militia

The Arkansas Territorial Militia was the forerunner of

today's Arkansas

National Guard. The current Arkansas

Army National Guard traces its roots to the creation of the

territorial militia of the District

of Louisiana in 1804. As the District of Louisiana evolved

into the Territory

of Missouri and the first counties were organized, Regiments

of the Missouri territorial militia were formed in present day Arkansas.

Territorial

Governors struggled to form a reliable militia system in the

sparsely populated territory. When the Arkansas

Territory was formed from the Missouri Territory, the

militia was reorganized, gradually evolving from a single

militia brigade composed of nine regiments to an entire militia

division composed of six militia brigades, each containing four

to six militia regiments. The local militia organization, with

its regular musters and hierarchy added structure to the

otherwise loosely organized territorial society. The Territorial

Militia was utilized to quell problems with the Indian Nations

and was held in readiness to deal with trouble along the border

with Mexico due to an ambiguous international border and during

the prelude to the Texas

War of Independence.

Creation

of a Territorial Militia

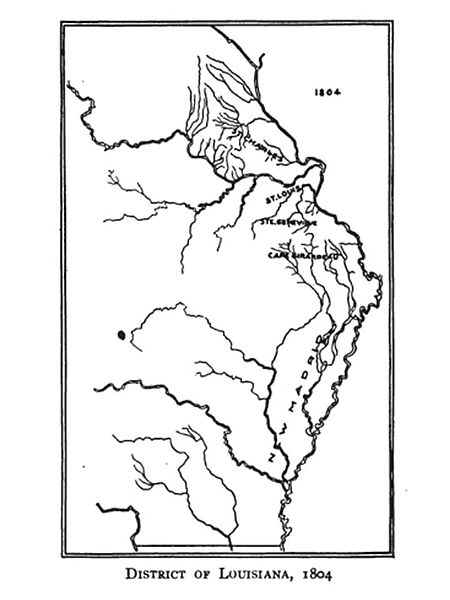

The history of the Arkansas militia began in 1804, when the

United States bought from France a huge tract of land west of

the Mississippi River. At the time of the transaction, now known

as the "Louisiana

Purchase", the area that would eventually enter the

Union as the State of Louisiana was referred to as the District

of Orleans. The area north of present day Louisiana was

referred to as the District

of Louisiana. At first the new "District of

Louisiana" was attached to Indiana

Territory for administrative purposes. In 1804 the District

of Louisiana was designated as the Louisiana

Territory and the new territory was subdivided into

districts – namely, St. Charles, St. Louis, Ste. Genevieve,

Cape Girardeau, and New Madrid – stretching along the Mississippi

River with no definite boundaries to the west. The area of

the present State of Arkansas

lay within the District of New Madrid, which stretched from the

present Arkansas-Louisiana state line to the present city of New

Madrid, Missouri.[1]

The authorities found that there were few people in the new

territory, especially the area which was later to become

Arkansas, to enroll in the militia. Low and swampy, early

Arkansas attracted few settlers, and many of those who did come

were itinerant French hunters and trappers who were hardly

temperamentally fit for the militia, which required a fairly

settled population. In 1803 a census of the two major settlement

areas in Arkansas, Arkansas Post and Ouachita, was carried out.

The census, about which there is much doubt as to its validity,

"estimated" that the Post District had a population of

600 with a militia of 150. The Ouachita District had

approximately 1,200 whites, 100 blacks, and a militia force of

300.[2]

Militia

law of the District of Louisiana

In October 1804, the governor and judges of Indiana Territory

met as a legislative body to begin the process of formulating

laws for the huge District of Louisiana.[3]

It is from this date that the Arkansas

National Guard tracks its earliest formation.

The Militia Act of 1804 contained 24 subsections. It made all

males between the age of 16 and 50 liable for militia

service excepting superior court judges, supreme court judges,

the attorney general, the supreme court clerk, all licensed

ministers, jail keepers, and those exempted by the laws of the

United States.[4]

The act laid out the number of officers required for each

company, battalion and regiment and required privates and

officers to arm themselves “with a good musket, a sufficient

bayonet and belt, or a fuse, two spare flints, a knapsack, and a

pouch with a box therein to contain not less than twenty-four

cartridges, .... knapsack, pouch, and powder horn, with twenty

balls suited to the bore of his rifle, and a quarter of a pound

of powder”. Companies were required to muster every other

month, Battalions in April and Regiments in October. Militiamen

who failed to attend muster would be fined after being tried by

court martial, which the commanders were given authority to

convene. The act also created the office of Adjutant General and

detailed his responsibilities.[5]

Volunteer

companies

The new law had forty-two sections, and one of the most

important sections of the law allowed for the formation of

volunteer companies.

These independent companies were the only units in the

militia that were to be issued standardized uniforms, arms and

equipment. Formation of independent of volunteer companies would

become an important part of antebellum society. While there are

very few records of any governor during the territorial or

antebellum period turning out an entire militia regiment for

service other than the required musters, there are ample

examples of volunteer or independent companies turning out for

service during times of war or conflict with the native

Americans.[6]

The

Arkansas District, Territory of Louisiana

By 1806, the lower two thirds of the District of New Madrid

was re-designated as the District of Arkansas;[7]

the area had two militia units: one cavalry company and one

infantry company. Despite the small population, it appears that

the early Arkansans enrolled in the militia in fairly large

numbers.[8]

A roster of militia appointments for the District of Arkansas

dated July 14, 1806 shows the officers

to have had a heavy French immigrant composition:[9]

- Major Francois Vaugine

- Captain of Cavalry Francois Valier

- Lieutenant of Cavalry Jacob Bright

- Cornet Pre. Lefevre

- Captain of Infantry Leonard Kepler

- Lieutenant of Infantry Anthony Wolf

- Ensign Charles Bougie.[10]

The same roster indicates that the Arkansas District militia

had its own "inspector and adjutant general", Major

David Delay. Other than this roster and a few other minor

references, the militia of the District of Arkansas, Louisiana

Territory, left few records.[10]

Militia

law of the Territory of Louisiana

In 1807, the legislature of the Louisiana

Territory passed an updated and expanded Militia Act. The

new law had forty-two sections. The maximum age of inhabitants

who were required to serve was reduced from 16–50 to 16–45.

Militia Officers were now required to wear the same uniform and

the United States Army. It increased the frequency that

companies were to muster up to 12 times per year, battalions six

times, and regiments twice. It created the office of Brigade

Inspector and set the pay of the Adjutant General at $150 per

year. The procedures for courts martial and the collection of

fines and other punishments were significantly expanded; fathers

were held liable to pay the fines of sons, up to the age of 21,

who failed to attend muster; officers were required to attend

training sessions to be conducted on the Monday before a

scheduled muster in order to receive training regarding their

duties and on the proper forms of drill. The legislature

indicated that where its laws were not detailed enough, militia

leaders were to look to the regulations of Barron Steuben which

had been adopted by Congress in 1779.[11]

Service

in volunteer companies encouraged

Section 37 of the Militia act of 1807 again addressed the

formation of independent or volunteer companies:

When in the opinion of the commander-in chief, such corps

can be conveniently raised and equipped, independent troops of

horse and companies 'of artillery, grenadiers, light infantry,

and riflemen may be formed, which shall be officered, armed,

and wear such uniform as the commander-in-chief shall direct.[12]

Service in these voluntary companies was encouraged by

exempting members from fines for failure to attend musters of

the regular militia and "[e]very trooper who shall enroll

himself for this service, having furnished himself with a horse,

uniform clothing and other accoutrements, shall hold the same

exempted from taxes, and all civil prosecutions, during his

continuance in said corps".[13]

Militia

Act of 1810

The legislature of the Louisiana Territory amended the

militia law in 1810 to provide for an Inspector General of the

Militia with an annual salary of $250. At the same time the

legislature did away with the salary of the post of brigade

inspector and reduced the number of times that the militia would

drill each year to six. The legislature also repealed the

requirement for officers to meet on the Monday for training

before a muster.[14]

Arkansas

County, Missouri Territory

On June 4, 1812, Louisiana

Territory was renamed Missouri

Territory.[15]

A little more than one year later, on December 31, 1813,

Governor of the Missouri Territory, William

Clark, signed a proclamation re-designating the District of

Arkansas as Arkansas County of Missouri Territory.[1]

The

Militia Law of the Missouri Territory

The legislature of the new Missouri Territory quickly enacted

a new Militia law. The Missouri Territory Militia act of 1815

included 47 sections and changed the service requirements.

"Every able bodied, free white male inhabitant of this

territory, between the ages of eighteen and forty-five years,

shall be liable to perform militia duty."[16]

This was the first reference to the race or status of militiamen

in the territorial militia laws.[17]

The act, like the previous militia laws, provided for the

formation of volunteer companies in addition to the standard

militia regiments and provided for the horse and other equipment

of members of these volunteer companies to be tax exempt.[18]

The militia law was amended in 1816 to clarify those persons

exempt from militia duty, clarify the duties and account

responsibility of paymasters, clarify court martial procedures

and to provide for the collection of fines levied by courts

martial by the sheriff or constable.[19]

The Militia law was amended again in 1817 to provide for payment

of those members detailed to sit on courts martial, to set the

fine for failure to appear at muster at two dollars, and to

allow the sheriff a fee of ten percent for collection of fines

imposed by the militia courts martial.[20]

The

first regiments formed in Arkansas

By 1814, the militia of Arkansas County was designated as the

7th Regiment, Missouri Territorial Militia.[21]

The officers were:[22]

- Lieutenant Colonel Commandant – Anthony Haden

- Major of 1st Battalion – Daniel Mooney

- 1st Company: Alexr Kendrick Captain, William Glassen

Lieutenant, William Dunn Ensign

- 2nd Company: James Scull Captain, Peter Lefevre

Lieutenant, Charles Bougy Ensign

- 3rd Company: Samuel Moseley Captain, Lemuel Currin

Lieutenant

- Major of 2nd Battalion – ???

- 1st Company: Edmund Hogan Captain, John Payatte

Lieutenant, Joseph Duchassin Ensign

- 2nd Company: Jno C Newell Captain, Benja Murphy

Lieutenant, Geo Rankin Ensign

- 3rd Company: William Berney Captain, Isaac Cates

Lieutenant, Saml Gates Ensign

In early 1815 Lawrence

County was created in the area of present day northern

Arkansas and southern Missouri.[23]

The establishment of new counties had an impact on the militia

since it was usually organized by county. The creation of

Lawrence County necessitated the appointment of a separate

commander for the county militia. On January 22, 1815, Missouri

Governor William Clark commissioned Louis de Mun a lieutenant

colonel and commandant of the 18th Regiment Missouri Militia. De

Mun, who had command responsibility for all of Lawrence County,

was ordered by the governor to "discharge the duty of Lt.

Colonel Comdt. by doing and performing all manner of

things..."[24]

War of 1812

25 Members of the 7th Regiment, Arkansas County, Missouri

Territorial Militia filed claims for pay for services rendered

during the War

of 1812.[25]

The petition claimed that the militia men were called into

service in May 1813 and that they had served for three months

under Captain Daniel M. Boon, David Musick and Andrew Ramsay.

The petition alleged that the militia men had been formed in to

companies containing 108 men each and that they had not been

paid for their services.[26]

Among the claimants who signed a petition requesting his pay was

Edmund Hogan,[27]

who was a resident of what would become Pulaski County and who

would eventually be appointed as the Brigadier General of the

Arkansas Territorial Militia.[28]

No records appear to exist of this unit being called out for

service during the War of 1812.

|

| http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arkansas_Territorial_Militia#Arkansas_Territory |

|

Arkansas

Territory

On March 2, 1819, President James Monroe signed the bill

creating Arkansas Territory. The act which created Arkansas

Territory provided that the territorial governor "shall be

commander-in-chief of the militia of said territory, shall have

power to appoint and commission all officers, required by law,

be appointed for said territory..."[29]

At the time of its formation, the new Territory of Arkansas

included the following five counties:[30]

- Arkansas

- Lawrence

- Clark

- Hempstead

- Pulaski

First

militia regulations published

Governor Izard worked to whip the militia into shape. He and

Brigadier General Bradford pleaded with local commanders to take

their responsibilities seriously. Noting that Arkansas lay

directly in the path to be used in the removal of the Eastern

Indians, the governor spoke frequently of the need "to

place the Militia in a condition to afford immediate protection

to our settlements, should any disorder attend the passage of

those people."[76]

Governor Izard’s agitation slowly began to get results. In

1825 the legislature authorized the printing of the militia laws

of the territory, with a copy of each to go to every officer in

the militia.[76]

Izard issued three militia reorganization plans in his three

years as governor. He worked to regularize musters, established

a regimental organization, and tried to improve the officer

corps by forcing the resignation of officers who failed to

attend musters, left the territory for more than three months,

or who failed to send their strength reports. Finally, in

November 1827, a bill passed providing for the first complete

overhauling of the militia. The act organized the forces into

two separate brigades, provided that battalions were to muster

annually and companies were to assemble twice yearly, and

established an administrative framework to oversee the

organization.[77]

Izard’s periodic reorganization orders,[78]

combined with legislation, resulted in the formation of a much

more effective militia system for Arkansas Territory.[78]

Militia

divided into two brigades

The Militia

Act of 1792 had specified how the state militia units were

to be organized:

On November 21, 1829, the Arkansas Territorial Legislature

passed an act dividing the Arkansas Territorial Militia into two

brigades.[84]

In April 1830, the United States Congress authorized the

Arkansas Territory a second Brigadier General to command the

second brigade of Arkansas Territorial Militia.[85]

On April 22, 1830 President Andrew Jackson nominated William

Montgomery to command the 2nd Brigade of Arkansas Militia.

|

| http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arkansas_Territorial_Militia#Arkansas_Territory |

|

Conflict

with Native Americans

When Arkansas became a territory in 1819 there were several

thousand Indians living in the area. Early Arkansas settlers

perceived these Indians as dangerous savages. Most of the

tribes, the Quapaw,

Caddo,

and Cherokee,

were in actuality quiet and peaceful. Problems also ensued along

the Territorial boundary with the Indian nation, with whites and

Indians each wandering across the ill defined border. The first

recorded clash between the Territorial Militia and Native

Americans apparently occurred in 1820. Captain George Gray,

Indian Agent for the Cherokee Nation at Sulphur Fork, wrote to

Secretary of War John

C. Calhoun regarding a claim by the Cherokee Nation that

they had been driven from a village along the Red River by two

companies of the Arkansas Militia.[87]

No records exist indicating whether this action was directed by

the Territorial Governor or was done under the control of local

authorities.[88]

Mr Calhoun responded to the claim and stated that he lacked

sufficient evidence to approve the Cherokee claim for damages

resulting from the loss of their villages but pointed out that

he could not protect Cherokees if they established villages in

areas assigned to whites by treaty.[45]

The

Pecan Point Campaign

The Osage

tribe, who ranged over much of northwest Arkansas, were a fierce

and warlike plains tribe. Mounted on their ponies, the Osage

frequently attacked villages of neighboring Indian tribes.

Occasionally white settlers would fall victim to the Osage. In

March 1820 Reuben Easton, a practically illiterate Arkansas

settler, wrote to the War Department complaining of the Osage

menace: “There has been a number of murders committed on this

river by the Osage indians and a vast number of Robbearys for

which the people heir has never Received any Satisfaction...”[89]

The Cherokee, who were given a reservation on lands claimed by

the Osage, were a more constant target of their warlike

neighbors.[90]

Governor George

Izard, who succeeded Miller in 1825, attempted to deal

calmly with the Indians. But he was still an old military man,

and when trouble between Indians and whites broke out in Miller

County in 1828, Izard sent his adjutant general, Wharton Rector,

to investigate. Forty-four Pecan Point citizens petitioned

Governor Izard on March 20, 1828 asking for protection from

hostile Indians.[91]

The petition stated that Shawnee and Delaware Indians near the

little Miller County settlement of Pecan Point were

"pilfering farm houses and Corn-cribs [,] killing Hogs,

Driving their Stocks and Horses and Cattle among us ...."

If the Indians were not removed, the settlers protested, there

was "no prospect but of being oblidged [sic]

to abandon our homes and fields."[92]

Major John

Goodloe Warren Pierson, commander of the Miller County

militia, asked the governor for permission to call out his

company to move against the Indians. The governor, instead, sent

Adjutant General Rector to investigate and if necessary "to

remove immediately [the Indians], and should they disobey or

resist your authority you will call out such a party of the

militia as you may consider adequate to compel obedience".[92]

When Rector reached Pecan Point he found the settlers greatly

agitated. The Indians were reported to be stealing and killing

livestock and threatening war. Rector immediately ordered the

Indians to leave the area, but the Shawnees refused. Calling out

sixty-three militiamen under Major Pierson, Rector marched on

the main Shawnee village. Just when a battle seemed imminent,

the major Shawnee chief announced he would move.[93]

The entire Pecan Point foray, about a week in duration, cost the

Arkansas militia a total of $503. Governor Izard, in

requisitioning reimbursement from the Secretary of War, detailed

costs as follows: Adjutant general’s salary (for a full month)

and expenses, $231; pay for one Major for four days, $12; pay

for five company officers for three days, $30, pay for 56

privates for three days, $168, rations for all men were a total

of $24.[91]

While there were no real battles between the Indians and the

Arkansas Territorial militia, the militia did send units on

several different occasions to perform patrol duty along the

state’s western border.[91]

|

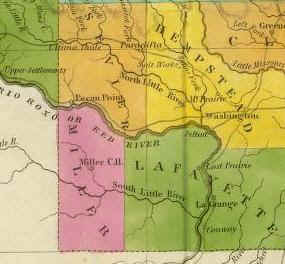

1835 map of Miller County, Territory of Arkansas,

including Pecan Point |

|

| http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arkansas_Territorial_Militia#Arkansas_Territory |

|

Governor

John Pope, 1829–1835

President Andrew

Jackson appointed John Pope to become the third Governor of

the Arkansas Territory on March 9, 1829. Pope was a Kentuckian

who, due to the loss of an arm as a youth had no prior military

experience. On 12 June 1833, Governor Pope appointed William

Field to serve as Adjutant General.[97]

Tensions

with Mexico

Next to the Indians, the Arkansans were most fearful of their

Mexican neighbors in Texas. Much of this trouble was caused by

an ill-defined boundary between Arkansas and Texas. The

International Boundary between the Arkansas Territory of the

United States and the Mexican state of Coahuila and Texas had

been defined in the treaty of 1819 between the United States and

Spain, but remained unsurveyed in 1827. Because the location of

the border was uncertain, the ownership of a considerable area

southwest of Red River was in question.[91]

Arkansas Territory had, since 1820, exercised jurisdiction over

the settlements immediately south of the river, holding them to

be a part of Miller County. In 1827 the easternmost portion of

the disputed area, approximating the present corner of Arkansas

southwest of the river, was assigned by the territorial

legislature to the new county of Lafayette. In 1828 Miller

County north of the river was abolished and a new Miller County

constituted south of the river in what is now northeastern

Texas.[98]

Miller County, as defined by the Arkansas territorial

legislature in 1831, comprised all the present northeastern

Texas counties of Bowie, Red River, Lamar, Fannin, and Delta

plus parts of eight counties south and west of these.[99]

The Mexicans, naturally, were fearful of the ever-encroaching

Americans, and on several occasions feelings ran high between

the suspicious neighbors. In 1828, for example, when the Miller

County militia was called out to remove the Shawnees from Pecan

Point, Mexican officials reminded the Arkansans that the area

was claimed by Mexico. Arkansas Adjutant General Rector warned

the Mexicans not to interfere. Rector threatened to hang the

Mexicans officials "on a tree by the neck like a dog."[100]

Two years later the Mexicans rubbed salt in the wounded pride of

the Arkansans by threatening to move Mexicans settlers into the

disputed Miller County area.[101]

Governor Pope reported to President Jackson on October 4,

1830, that "20 or 30 of our people" had taken the oath

of allegiance to Mexico, "& received certificates of

right to land with the territory here fore [sic ] occupied by

this government------" He also reported that the Mexicans

had dispatched a small force to establish a fort on Red River

and to prevent American from entering Texas.[102]

As a precautionary measure Pope had ordered regimental musters

of the territorial militia "& warned our citizens . . .

against taking title or protection" from the Mexican

government. The Arkansas Gazette reported October 13, 1830, that

Pope had recently made a two weeks excursion to the southern

countries and reviewed the militia "at some of the

Regimental Musters." Governor Pope thought that the

Mexicans were "pressing their claim beyond the line

intended & contemplated by the negotiators of old Spain

& the United States---"[103]

The Gazette stated on November 3, 1830, that certain Mexican

officials had commenced surveying Mexican claims in the

disuputed border area on October 11 and that they intended to

continue until stopped by force of arms.[104]

On November 1, 1830, Brigadier General George Hill, commandant

of the 3rd Brigade of Arkansas Territorial Militia, reported to

Pope that Curtiss Morriss, a citizen of Lost Prairie, had

informed him that Mexican surveyor's were surveying the tracts

granted to persons who had taken the oath of allegiance to

Mexico, and that the Mexican claimants had threatened to

dispossess loyal Arkansas citizens who refused to take the oath

and whose land lay within the tracts of persons who had taken

the oath. These loyal territorial citizens claimed the

protection of the United States.[105]

Governor Pope immediately forwarded General Hill's

communication to the President. President Andrew Jackson,

formally protested Mexican actions in the disputed area and was

successful in getting Mexican Government authorities to stop

actions in the disputed area until the boundary could be

settled.[106]

The border area enjoyed a brief period of quite until just

before the Texas War of Independence.

Militia

re-organized into six brigades

On November 16, 1833, Governor Pope signed a bill from the

Territorial Legislature which divided the territorial militia

into six brigades and formed them into a new division.[111]

Each new brigade was authorized a Brigadier General to command.

The new Brigadiers were required to renumber the regiments

within their respective brigades and report this number to the

Major General commanding the division.

Governor

William S. Fulton, 1835–1836

William

S. Fulton was appointed by President Andrew Jackson to

become the fourth and final Territorial Governor of Arkansas on

March 9, 1835. He served until he was replaced by the first

elected governor of the new state of Arkansas in 1836.[137]

Renewed

tensions with Mexico

Troubles along the border with Mexico flared again during the

Texas

War of Independence Brigadier General George Hill was

informed on May 4, 1836 that information had been received

indicating that Mexican emissaries were trying to incite the

Indian Nations to attack in retaliation for United States

support of Texas

War of Independence. Governor Futon directed Brigadier

General Hill to place organize his brigade and place it in

readiness to take the field at once. On June 28, 1826, General

Edmund P. Gains (U.S. Army) called upon Governor Fulton one

regiment for the defense of the western frontier. Twelve

companies would eventually answered this call.[138][139]

Still, as with the Indians, there was no open military

conflict between the Arkansas Territorial militia and the

Mexican Government before the Arkansas Territory achieved

statehood on June 15, 1836.

|

| http://peace.saumag.edu/swark/articles/ahq/miller_co/artxborder/artxborder95.html |

|

ARKANSAS HISTORICAL

QUARTERLY; Volume 19, Spring

1961,p. 95

-

Disturbances on the

-

Arkansas-Texas Border,

-

1827-1831

-

-

BY LONNIE J. WHITE

-

Austin, Texas

-

- The International Boundary between the Arkansas Territory

of the United States and the Mexican state of Coahuila and

Texas had been defined in the treaty of 1819 between the

United States and Spain, but remained unsurveyed in 1827.

Because the location of the border was uncertain, the

ownership of a considerable area southwest of Red River was

in question. Arkansas Territory had, since 1820, exercised

jurisdiction over the settlements immediately south of the

river, holding them to be a part of Miller County. In 1827

the easternmost portion of the disputed area, approximating

the present corner of Arkansas southwest of the river, was

assigned by the territorial legislature to the new county of

Lafayette. In 1828 Miller County north of the river was

abolished and a new Miller County constituted south of the

river in what is now northeastern Texas (1).

- ______________________

- 1. Rex W. Strickland, "Anglo-American Activities in

Northeastern Texas 1803-1845" (unpublished Ph.D.

- dissertation, University of Texas, 1937, 95-96, 101-102,

170-175; Rex W. Strickland, "Miller County, Arkansas

Territory, The Frontier that Men Forgot." Chronicles

of Oklahoma, XVIII (March, 1940), 12: Grant Foreman, Indians

& Pioneers (Norman, 1936), 230: Arkansas Acts.

1827, pp. 10-11. According to Strickland. Miller County, as

defined by the Arkansas territorial legislature in 1831,

comprised all the present northeastern Texas counties of

Bowie, Red River, Lamar, Fannin, and Delta plus parts of

eight counties south and west of these.

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|